Dogtown legend Peggy Oki is fighting to protect our oceans

- Text by Caroline Ryder

- Photography by John Francis Peters

Peggy Oki sits in a coffee shop in Venice Beach, California, among cool people working on their MacBooks to a cool ’80s New Wave soundtrack. She looks around and quietly takes it all in – things have changed. When she was skating these streets in the ’70s, the only female on the zeitgeist-shifting Zephyr skate team, the area was a rough- edged beach community populated by gangbangers, hippies, Vietnam vets, and the odd tripped-out actor (think Dennis Hopper). No one had any idea that she and the Z-Boys – Jay Adams, Tony Alva, Stacy Peralta, her compadres from Jeff Ho’s Zephyr skate shop – were inventing a global youth culture phenomenon with each clack of their polyurethane wheels over the uneven sidewalk. “At the time, I couldn’t have imagined having the sort of fame that I do now,” she says, sipping on a big cup of rooibos tea. “It’s been so many decades now since we were skateboarding, seeking fun and adventures. And those days still have importance. You know that phrase, ‘Who woulda thunk?’ I think about that a lot. Who woulda thunk.”

Zephyr was, without doubt, one of the most influential teams in skateboarding history, the Dogtown legacy immortalised in the photographs of C.R. Stecyk III and Glen E. Friedman, Stacy Peralta’s award-winning documentary, Dogtown and Z-Boys (2001), and Catherine Hardwicke’s film Lords of Dogtown (2005, starring Heath Ledger and Emile Hirsch). There are approximately 11 million active skaters in the world today, practising tricks pioneered by Oki and her buddies, creators of the new era of surfer-style skateboarding that still dominates today.

People often ask her what it was like being the only girl on the team. Was it weird? Were there other girls skating? (There weren’t.) But Oki never saw herself as different. “I just knew that I loved skateboarding. I wanted to skate, and these guys wanted to skate, and that’s all we focused on.” If there was attention drawn to her by virtue of her gender, she didn’t pay it much heed.

Photo by Pat Darrin

When Adams died of a heart attack in August last year, it came as a surprise to Oki. Adams had spent much of his life in and out of jail, battling drug addiction, but seemed to have closed that chapter. That he would pass almost immediately after conquering his demons seemed, at first, a cruel twist of fate. Then when she thought about it for a while, it made sense. “At least when he passed he was in a higher state of consciousness; he was with his wife and friends, on a surf trip. He had some of the best waves in his life.”

She’s a surfer, too, and has been her whole life. It was in the water that she found her second calling, after skating. She was surfing in Ventura and was waiting for some waves when a dolphin swam up to her. “He was maybe ten feet away, and lifted his head and looked right at me.” So moved was Oki, she went home and painted a canvas recreating the moment – that intelligent eye looking into hers before plunging back underwater. She decided to focus on studying dolphins, and left Los Angeles for Santa Barbara, a hundred miles up the Pacific Coast Highway. At the university there, she studied biology, concentrating on dolphin behaviour in the wild. “Scientists at that time were saying that play is a surefire sign of intelligence, and I had seen the dolphins playing, surfing the waves alongside us. I always felt that to be a common bond between surfers and dolphins.”

Some years later, another encounter with a sea mammal pushed her life further in the direction of conservation. She was surfing at the secluded Black’s Beach near La Jolla on Christmas morning 1999, the last holiday of the Millennium. The conditions were beautiful, excellent waves and very little wind. But everyone was at home unwrapping gifts, and Oki had the beach to herself. She paddled out and waited for the next wave. In the distance, about a mile down the coast, she noticed some spouting, and figured it was probably gray whales heading southward on their annual migration. Then, about twenty feet away from her, a gray whale “spy-hopped,” raising its head vertically like a periscope out of the water, and looked right at her. “I went whoaaaa,” says Oki. “And then it went back down. Then another whale came back up. I saw this beautiful arching back and thought, ‘They know something about me.’ I felt like I was being called to do something.”

She found out that there was an environmental battle going on, not too far away – Mitsubishi and the Mexican government were trying to build a salt-mining facility in a tranquil lagoon in the palm oasis town of San Ignacio, a couple hundred miles away in Baja California Sur. The pretty lagoon happens to be one of the key nursing and calving grounds for gray whales. “I said, ‘This can’t happen.’” She joined the eventually successful campaign to block the salt mine, but soon discovered that whales were still being killed the world over. “I had no idea. I thought whaling had ended in 1986. When I heard that Japan and Norway were out there hunting whales and killing a lot of them, I knew I had to do something.”

“Another whale came back up. I saw this beautiful arching back and thought, ‘They know something about me.’ I felt like I was being called to do something.”

She starts folding a square piece of notepaper on the table, showing me how to make an origami whale. “You fold it on the diagonal, then you open it and you have a taco fold. Then you bring the edges to meet the fold in the centre and you do the same thing with the other side and it looks like a kite, and then we bring the points together.” Peggy Oki, with help from the public, made a giant curtain comprising 38,000 origami whales – a moving memorial to every whale killed since 1986. The curtain, sadly, will likely grow by 2,000 whales each year, says Oki. It’s part of the activism that now consumes much of her life, her efforts devoted to trying to save the thousands of whales that are killed each year, and the 20,000 or so dolphins. She encourages everyone to watch the movies The Cove and Blackfish, as disturbing but necessary primers on the slaughter that is happening in the water, and speaks regularly at universities and festivals. Being Japanese American, with parents who were born and escaped from Hiroshima, she is upset at the policies of her motherland but does not blame the Japanese people. It’s just a small group of money-minded human predators turning the water red, she says.

She’s still an active surfer and skater, although she doesn’t skate pools or ramps anymore thanks to an injury seven years ago at Santa Paula park. “I was skating better than ever at the time,” she recalls, “then I went for a frontside grind and wiped out… but instead of sliding on my kneepads I landed like a cat on my feet.” She damaged her knee cartilage so badly it put her out for a year. She couldn’t even pedal a bicycle. “I love mountain biking and surfing and rock climbing, and I thought, ‘Is it really worth it to miss out on all these other things because of skateboarding?’” So she still rides her cruiser board around, and tries to avoid skateparks, not because she’s scared – quite the opposite. “My problem is, I enjoy it too much,” she says, laughing. “I’m not very good at just reigning myself in. I always want to do more.”

This limitless drive sees Oki constantly building on her ambitions. Right now, the line-up of active campaigns that she’s either initiated or supports keeps her on the frontlines of some of the world’s most charged conservation battles. In New Zealand, there are the critically endangered Maui’s and Hector’s dolphins to save; in Miami there’s Lolita, a lone orca who’s spent forty-four years caged inside a man-made tank. And then there’s the arduous but rewarding task of educating the next generation, a longer-term goal that she’s constantly working towards through her self-initiated Whales and Dolphin Ambassador programme, which teaches kids and teenagers about “anthropogenic (human-caused) threats to cetaceans and their ocean habitats”.

That’s a big old mission, right there. Whether she’s protecting a single whale, or helping an entire species fight for survival, Oki notes that much like skateboarding, activism is all about the end game. There are no instant results, just months and months of work and effort, in the hopes of something good. “You have to be determined as a skater if you’re going to get a frontside grind on the coping in the pool. You have to keep at it. It’s the same with being an activist. You don’t win victories easily.”

Find out more about Peggy’s ocean activism.

This article originally appeared in Huck 49 – The Survival Issue. Grab a copy in the Huck Shop or subscribe today to make sure you don’t miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

In the ’60s and ’70s, Greenwich Village was the musical heart of New York

Talkin’ Greenwich Village — Author David Browne’s new book takes readers into the neighbourhood’s creative heyday, where a generation of artists and poets including Bob Dylan, Billie Holliday and Dave Van Ronk cut their teeth.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

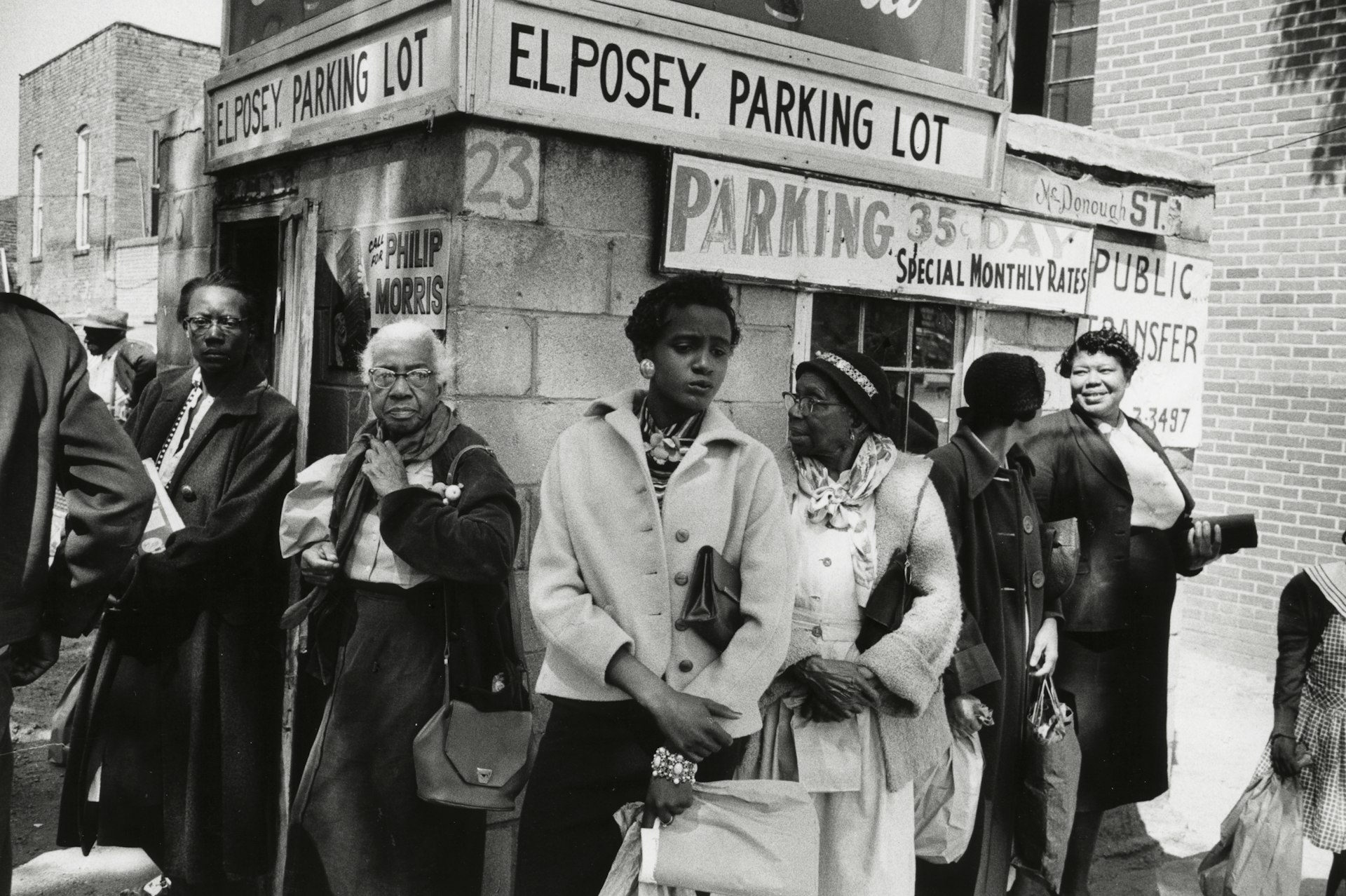

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk