The student movement fighting to cancel exams in England

- Text by Daisy Schofield

- Photography by Fran Hales, 2020

Amir Asfour*, a 16-year-old BTEC student from London, has spent most of his Christmas break feeling sick with worry. On top of spending his first Christmas apart from his mum, who was busy working as an NHS nurse, Asfour’s teacher was diagnosed with COVID-19 at the start of last November. This same teacher – who was supposed to be preparing students for an exam this January – has not returned to her job since falling ill.

“We had a supply teacher, but they didn’t even specialise in the subject,” explains Asfour. “Me and my classmates have no idea how to use the learning content – it’s just words on a screen.” It has thrown his entire future into the balance: “I’d wanted to go to uni in Liverpool, but now, I’m having to rethink.”

“Our futures matter too,” he continues, “but we seem to be the ones paying the price for the government’s mistakes.”

Asfour’s fears and frustrations are shared by countless students across the country who’ve had their lives and their studies upended by the pandemic. Now, they are expected to return to their classrooms amid soaring cases of COVID-19, as pressure mounts on the government to close all secondary schools following its U-turn on primary school closures last week.

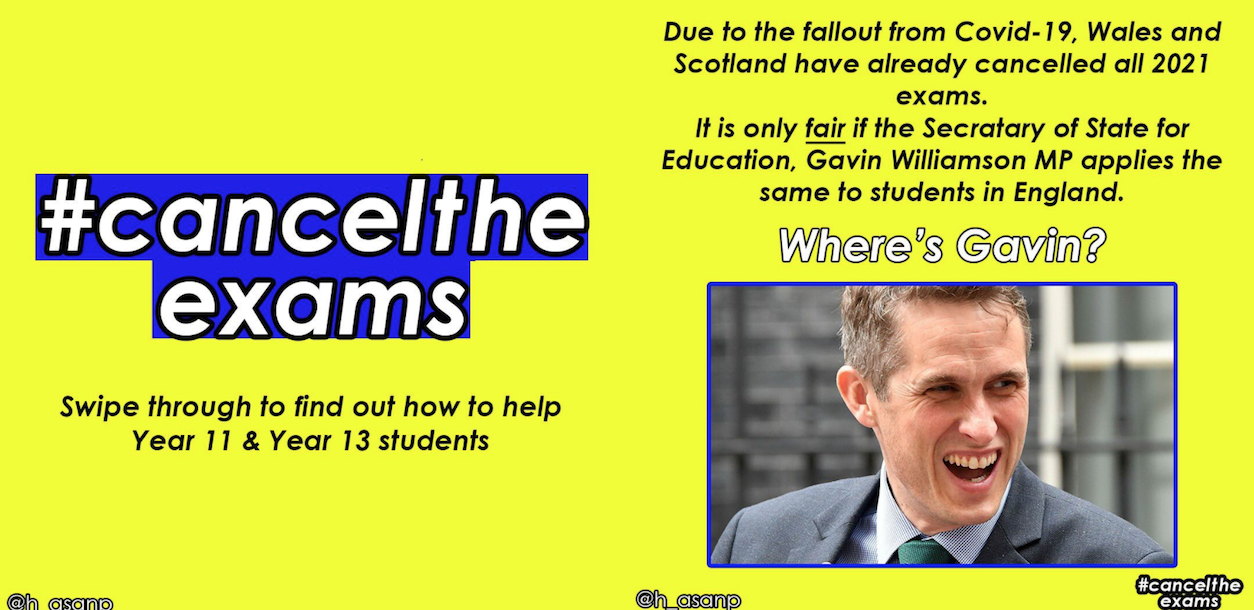

While the government has delayed the reopening of secondary schools across most of England by one week for exam-year pupils and two weeks for other school students, the education secretary Gavin William is insisting that higher exams will go ahead as planned. This is despite Scotland and Wales last year announcing the cancellation of GCSE and A-Levels exams in 2021.

In England, end of year exams will be slightly delayed, and pupils will be given advance notice of some topics ahead of their tests. But for many students, these measures don’t go anywhere near far enough – particularly for BTEC students such as Asfour, who are expected to sit their exams within weeks and have been repeatedly left out of the conversation.

Last month, just before Christmas, Hasan Patel, a 17-year-old student from London, launched the #canceltheexams campaign with an Instagram post that has since garnered over 82,280 likes. “We’re under enormous pressure to catch up on five months of lost education,” reads the post. “Many feel overwhelmed and at breaking point.”

via IG @h_asanp

The campaign is imploring people to “ramp up the pressure” on the Tory government by emailing their MP and signing the petition, ‘Cancel GCSEs and A Levels in 2021’ – which has so far amassed over 203,270 signatures. It has since triggered a flurry of similar campaigns across England, spread via Instagram. In Canterbury, a pair of students successfully convinced their MP, Rosie Duffield, to support cancelling exams after writing an open letter that was signed by 406 students in less than 24 hours.

In Patel’s post, the campaign sets out to defend “young people from disadvantaged backgrounds who have faced extreme difficulties” during the pandemic. Patel, who has been a recipient of free school meals his entire life, says he was “politicised by the impact of austerity”. He attended state school up until winning a fully-funded scholarship to Eton for sixth-form – something that has made him acutely aware of the gaping inequalities which plague the UK’s education system.

These inequalities have only been exacerbated by the pandemic. After being sent home from school in the first lockdown, Patel returned to the two-bedroom East London council flat he shares with his two brothers and parents. “When I got home, it was overcrowded, loud and noisy. I don’t have any space on my own to work,” he explains. “This made things very, very difficult for me. I did end up getting depression in lockdown.”

It’s a situation all too familiar for students across the UK who lack space to study at home, particularly in lockdown, where more family members are likely to be working remotely or recently made redundant. Tamira Kay*, an 18-year-old student from Bristol, has been studying at her dining room table since lockdown began. “My mum’s on furlough, my dad’s working remotely and my brother has been self-isolating froom school at home,” she says. “It’s a full-house, and I sometimes have zero motivation to work because it’s so distracting.”

Lacking access to laptops and the internet is another factor that has been hampering many student’s learning. Guy Lucas-Bhana, 17, says the problem has been particularly bad for state schools in his home county of Hertfordshire. “The tools to deliver remote learning weren’t in place as they have been from day one and came down to what an individual teacher could deliver,” he says. “This was entirely preventable, but the government has sold out teachers and students every step of the way.”

Compounding this are the huge disparities in the amount of classroom time pupils have received across England. “Not all students are on a level playing field,” says James Wright*, a Year 11 computer science teacher from Bolton. “Areas of deprivation and inner cities have had higher COVID-19 cases, leading to a greater learning loss.”

“Exam grade boundaries are set based on how the whole cohort of students in the country performs,” Wright continues. “The grade boundaries are set after the exam, once all the marks are in. Grade boundary setting is fair if on the whole, all learners in the country have the same learning time.”

It’s more than just grades and university places that are cause for concern. Exams can have a devastating impact on students’ mental health. In a study conducted by YoungMinds investigating the impact of COVID-19 on secondary school pupils, 69 per cent of respondents described their mental health as poor since returning to school, while demand for the charity’s helpline is soaring among young people.

Patel says one student from Newcastle reached out to him shortly after he launched his campaign explaining how she’s had to deal with multiple bereavements through the pandemic. “She has tried to keep up with exams,” says Patel, “but has just reached a point of mental exhaustion.”

Wright, meanwhile, has seen firsthand the “immense stress” students are facing due to lockdown and bubble closures. “I have been with my year group for three years and have not had to deal with students having panic attacks. In the last half term, we had five students having panic attacks.”

There are, of course, students also who would like exams to go ahead – but these are students who may not have faced the same disruption to their learning. Patel says that because of his educational platform, he is confident he’d be able to get the grades he needs to get into uni. But, for so many students across the country, this is not the case: “It’s not about individuals – it’s a systemic problem,” he stresses.

chants of “fuck the algorithm” as a speaker talks of losing her place at medical school because she was downgraded. pic.twitter.com/P15jpuBscB

— huck (@HUCKmagazine) August 16, 2020

Another reason some are resistant to the idea of exams being cancelled is out of fear of a repeat of the A-Levels fiasco from last summer, which saw students downgraded over a bias algorithm. But those backing the #canceltheexams campaign insist that it simply cannot be a last-minute eruption of chaos where students are left worse off. Instead, there is potential for a similar system to Wales of internal in-class assessments – where students are told by teachers what topics to revise – to be implemented in England. There is also the possibility of teacher-assessed grades (although concerns have been raised that these are subject to bias), and setting students anonymised coursework over the summer.

The pandemic has brought the deep inequalities that have long existed within the country’s education system to the fore. For Patel, cancelling the exams may not be the solution – but it is a starting point. It’s an action that has the potential to stretch beyond the pandemic, sparking a national conversation about whether the UK’s exam system – where a set of tests determines many of people’s life choices – is fit for purpose.

For now, students are keeping on the pressure, with Patel proposing school strikes in the event that secondary schools do close, and exams become untenable. “Students aren’t just going to sit around and accept what the government says,” he says. “We’re going to take a stand.”

*Some names have been changed to protect identities

Daisy Schofield is Huck’s Digital Editor. Follow her on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Clubbing is good for your health, according to neuroscientists

We Become One — A new documentary explores the positive effects that dance music and shared musical experiences can have on the human brain.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

In England’s rural north, skateboarding is femme

Zine scene — A new project from visual artist Juliet Klottrup, ‘Skate Like a Lass’, spotlights the FLINTA+ collectives who are redefining what it means to be a skater.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Donald Trump says that “everything is computer” – does he have a point?

Huck’s March dispatch — As AI creeps increasingly into our daily lives and our attention spans are lost to social media content, newsletter columnist Emma Garland unpicks the US President’s eyebrow-raising turn of phrase at a White House car show.

Written by: Emma Garland

How the ’70s radicalised the landscape of photography

The ’70s Lens — Half a century ago, visionary photographers including Nan Goldin, Joel Meyerowitz and Larry Sultan pushed the envelope of what was possible in image-making, blurring the boundaries between high and low art. A new exhibition revisits the era.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The inner-city riding club serving Newcastle’s youth

Stepney Western — Harry Lawson’s new experimental documentary sets up a Western film in the English North East, by focusing on a stables that also functions as a charity for disadvantaged young people.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The British intimacy of ‘the afters’

Not Going Home — In 1998, photographer Mischa Haller travelled to nightclubs just as their doors were shutting and dancers streamed out onto the streets, capturing the country’s partying youth in the early morning haze.

Written by: Ella Glossop