A visual guide to the hidden history of hip hop

- Text by Miss Rosen

“Rap is something you do. Hip hop is something you live,” KRS One memorably said, reminding fans that the culture of hip hop is more than just an MC on the mic. Hip hop is a style, an attitude, and a way of life that transcends all boundaries, be it cultural or political, and brings people together in celebration of black power, pride, and principles.

At the foundation of hip hop are DJs, MCs, B-boys and B-Girls, and graffiti – which represent the music, literature, dance, and visual arts. Although MCing (aka rapping) has become the most famous element, it’s the fruit of a tree with much deeper roots, one that Rhea Combs, curator of photography and film, and director of CAAMA, explores in the new exhibition, Represent: Hip-Hop Photography.

Represent takes work from Bill Adler’s Eyejammie Hip Hop Photography Collection as its departure point, visually sampling from the seminal archive that includes more than 400 iconic photographs by 60 leading artists including Charlie Ahearn, Harry Allen, Janette Beckman, Al Pereira, and Jamel Shabazz. For the exhibition, Combs has paired these works with historical photographs and other objects from the museum’s permanent collection, to illustrate the ways in which the innovative practices can be found in African-American history decades before hip hop was born in the Bronx.

WOMEN RAPPERS © Janette Beckman

For example, a portrait of Queen Latifah appears alongside ’20s blues singer Gladys Bentley, drawing a striking parallel between the two women who have endured public scrutiny and media speculation about their appearances independent of their work. These pairings add new layers of context and depth in order to show how hip hop is a natural continuation of the black experience in America over centuries.

Bill Adler, a music historian and former publicist for Def Jam, started the collection, which continues to bear and preserve the name of the Eyejammie Gallery, which he ran in New York City from 2003 through 2007. “I was running this gallery and putting together these shows, but in effect, I was creating the collection,” he explains. “I did my best not just to exhibit the photos but to also sell the prints. I might have been a little too early with this.”

“In 2003, I did a show devoted to images of Run-DMC and I pegged it to the 20th-anniversary release of their first single. I had people come to see the show and they dug a lot of the photos but no one was buying anything. I imagine the thought process might have been, ‘Wait a minute. I saw this photograph for the first time in Right On magazine in 1984 and I paid $2.95 for the magazine and now Bill Adler wants me to pay $200 for a print?’”

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Chris DAZE Ellis, © DAZE

Although Adler didn’t sell many prints while the gallery was open, he created a solid collection of work that defined hip hop as it made its way on to the world stage. The collection, which was born out of Adler’s love for preserving music history and culture, was acquired by the museum in 2015.

“It has been tremendously gratifying to me for the museum to acquire the Eyejammie Collection because it confirmed my feelings about this material: that it was capital ‘A’ Art, capital ‘H’ History, and capital ‘C’ Culture and would continue to be of values in those ways,” Adler adds.

“Rhea had a really creative idea about what to do with my collection, and I was knocked out by it. Represent is a gem that speaks to the larger collection that the museum has – and it is nothing short of phenomenal.”

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, © Janette Beckman

KRS1 & Ms Melodie © Janette Beckman

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, © Janette Beckman

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Photo by Al Pereira, © Al Pereira

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Photo by Al Pereira, © Al Pereira

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Antwan Patton

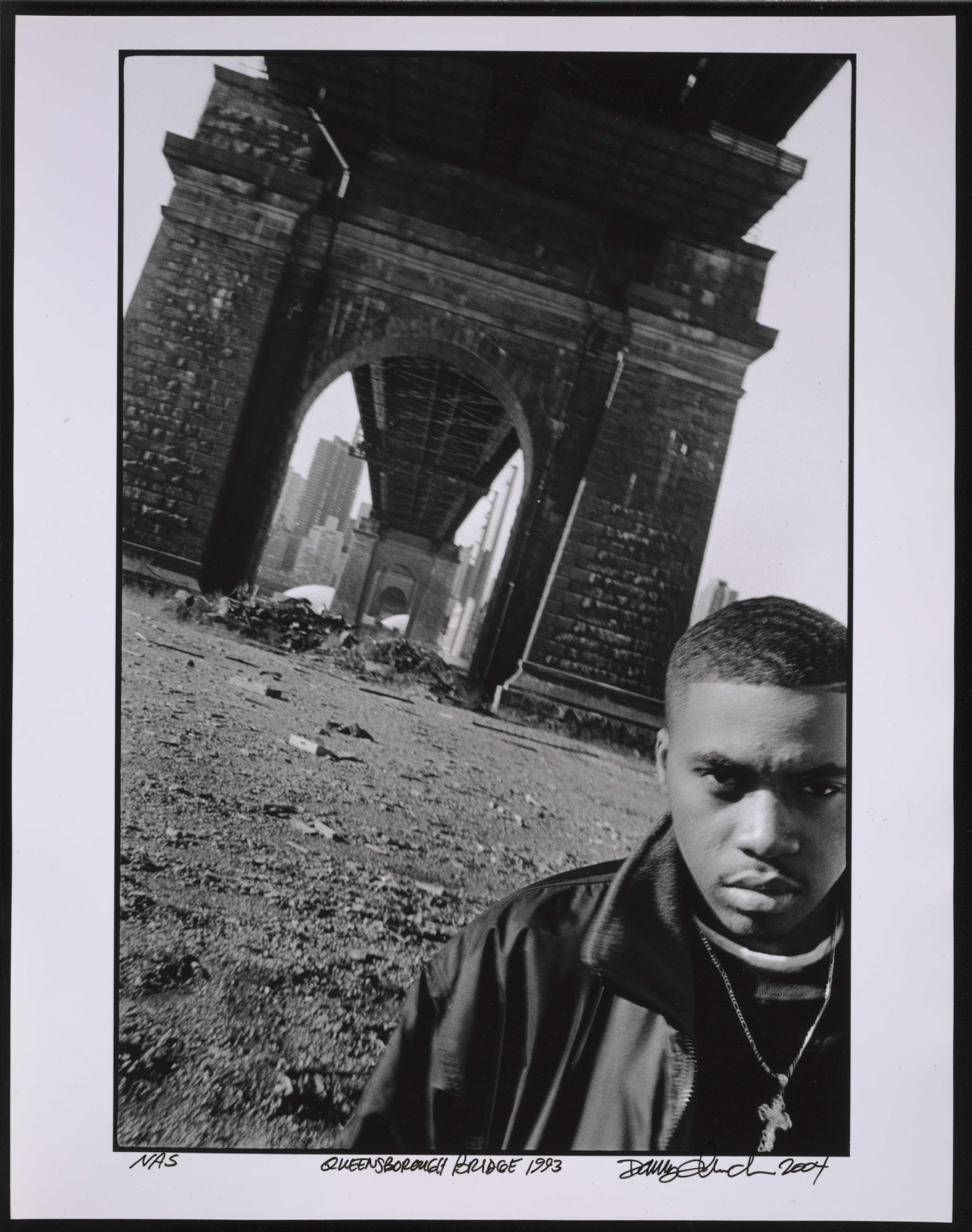

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment. Photograph by Danny Clinch. © Sony Music

Represent: Hip-Hop Photography is on view at the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, D.C., through May 3, 2019

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Clubbing is good for your health, according to neuroscientists

We Become One — A new documentary explores the positive effects that dance music and shared musical experiences can have on the human brain.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

In England’s rural north, skateboarding is femme

Zine scene — A new project from visual artist Juliet Klottrup, ‘Skate Like a Lass’, spotlights the FLINTA+ collectives who are redefining what it means to be a skater.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Donald Trump says that “everything is computer” – does he have a point?

Huck’s March dispatch — As AI creeps increasingly into our daily lives and our attention spans are lost to social media content, newsletter columnist Emma Garland unpicks the US President’s eyebrow-raising turn of phrase at a White House car show.

Written by: Emma Garland

How the ’70s radicalised the landscape of photography

The ’70s Lens — Half a century ago, visionary photographers including Nan Goldin, Joel Meyerowitz and Larry Sultan pushed the envelope of what was possible in image-making, blurring the boundaries between high and low art. A new exhibition revisits the era.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The inner-city riding club serving Newcastle’s youth

Stepney Western — Harry Lawson’s new experimental documentary sets up a Western film in the English North East, by focusing on a stables that also functions as a charity for disadvantaged young people.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The British intimacy of ‘the afters’

Not Going Home — In 1998, photographer Mischa Haller travelled to nightclubs just as their doors were shutting and dancers streamed out onto the streets, capturing the country’s partying youth in the early morning haze.

Written by: Ella Glossop