Photographers are revealing the dark truth about mass incarceration in the USA

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Steve Davis

In December 1967, photographer Danny Lyon stepped inside the Walls Unit prison in Huntsville, Texas. “It was evening and I had passed through the various control points, the massive locked entrance, then more gates and I was walking around inside the large prison yard entirely alone, with my Nikon F over my shoulder,” he told Huck in 2015. “The fox was inside the chicken coop and was going to stay there as long as he wanted.”

At the time, Danny was determined to put the issue of prisons on to the agenda. He hoped that revealing the brutality of the Texan prison system – still based on a format created during slavery, with inmates segregated and where officers and guards took on the role of all-powerful gods – in his 1971 book Conversations with the Dead could help create pressure for prison reform. He was wrong.

As he writes mournfully in the epilogue to the book’s re-release, the number of prisoners incarcerated in the US today is now 20 times what it was when he completed his landmark work. The intervening decades saw the rise of mass incarceration and the ‘Land of the Free’ became home to the greatest prison population on earth. Total US incarceration peaked in 2008, but the most recent statistics show there are still around 2.2 million people incarcerated in the US.

When photography has historically been such a powerful force for social change in the United States – highlighting injustices and galvanising resistance, from the Great Depression, to the Civil Rights movement and ending the Vietnam war – how has photography been so impotent to confront the rise of mass incarceration?

With access to prisons by photographers strictly controlled and prisoners themselves prevented from documenting their own realities, our understanding of prison life is too often clouded by blindness and misrepresentation. The Prison Photography project, run by writer Pete Brook, exists to celebrate photography that helps us see the true face of the American prison system.

In nearly a decade of documenting the photography of prisons past and present, Pete has come up against the limits of photography to represent the realities of such a complicated context, its power to create change and has come face to face with the scale of the challenge: overcoming mass incarceration requires not just prison reform, but confronting the major flaws in American society.

“Prisons are ours,” Pete explains. “Just like we feel the deserts, the prairies or the rivers are ours, prisons are part of the American landscape now. We need to deal with them and see them.”

Today, nearly one in 100 American adults still live behind bars, but the prison system was not always so all-consuming. Since 1980 the prison population has quadrupled. The War on Drugs’ rhetoric introduced by Richard Nixon in the 1970s, the subsequent federal policies enacted by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s which ripped up the safety nets for society’s most vulnerable and responses to the public safety panic in the 1990s, such as Three Strikes Laws and mandatory-minimum sentences, all contributed to a growing need for jail cells.Projects like Danny Lyon’s are rare and no photographer since has been given such unrestricted access. In prison, vision is power and a conscious effort has been made to restrict the images that get out. If photographers do gain access, we have to be critical of the work because it has ultimately been manipulated and censored by authorities who make all the rules inside the prison walls, Pete argues.

In that context, photographers have employed inventive tactics to overcame this immense gap in the representation of prison life and present truths unfiltered by the agendas of prison authorities. Pete’s 2014 Prison Obscura exhibition, highlighted some of the most powerful examples. For photographer Josh Begley, representing the scale of the issue represented the biggest challenge. In Prison Map, he chose to use data visualisation and satellite imagery of prison complexes across the country, to help viewers appreciate how immense the prison-industrial complex had become.

Despite prisoners making up a greater proportion of the population in America than any other nation on earth, Pete argues that they are the most voiceless group in society. Rarely are they seen as anything more than parades of orange jumpsuits. Photographer Alyse Emdur attempted to challenge this, capturing the infamous mural walls that have sprung up in prison visiting areas which often provide the backdrop to family members’ only images of inmates. “These images offer an opportunity to see America’s prison population, not through the usual lens of criminality, but through the eyes of inmates’ loved ones,” says Alyse.

Kimberly Buntyn, Valley State Prison for Women, Chowchilla, California; photograph courtesy Alyse Emdur. From the series Prison Landscapes (2005-2011). Photo: Anonymous, courtesy of Alyse Emdur.

Shawangunk Correctional Facility, New York. From the series Prison Landscapes (2005-2011). Photo: Alyse Emdur.

Photography workshops that allowed prisoners to document their own realities have all but disappeared since the 1980s, leaving us with a gap to see prison life through the eyes of those behind bare. Photographer Mark Strandquist attempted to get around these restrictions by taking photographs of scenes described by prisoners in letters to him, then mailing the results to them.

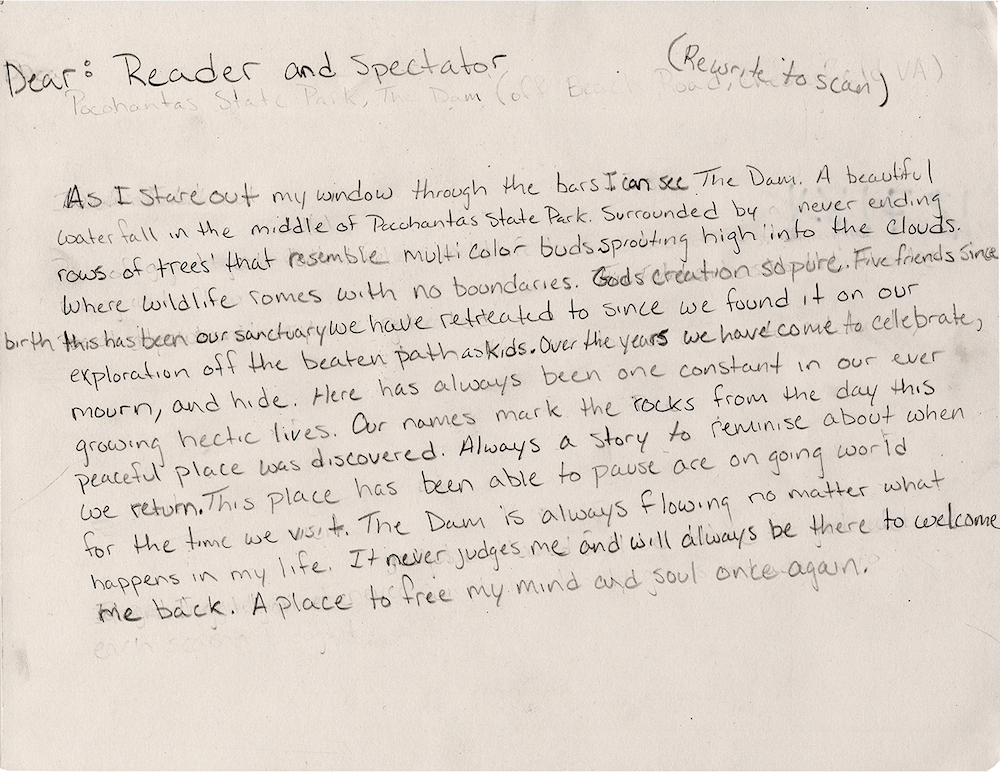

A prisoner’s text describing a dam in Pocahontas State Park. Artist Mark Stradnquist then made a photograph of the dam and gifted it to the prisoner. When exhibited, Strandquist partners with local prison reform groups to program events and education about mass incarceration, community and solutions. From the series Windows From Prison by Mark Strandquist.

Image of a dam, made in response to a description provided by a prisoner in Richmond County Jail, Virginia. From the series Windows From Prison by Mark Strandquist.

Yet, despite these inventive approaches, Pete argues that prison photography reveals the limits to photography and photojournalism’s ability to highlight, the reality and injustice behind bars, and power movement toward reform. “I’m not confident in saying any photographer has successfully changed national debate,” Pete explains. “Where is the Abu Ghraib photo of American prison system? But when we’ve all seen footage of officers choking Eric Garner to death and watch Philando Castile bleeding out after being shot by police, yet seen no meaningful change. In that political visual sphere, it seems unreasonable to expect images to change an entire system.”

While Pete has been confronted with the limits of photography’s power, the project has also made him realise how far-reaching the logics that drive mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex are. They are ultimately symptomatic of a severely broken society.

Incarcerated girls at Remann Hall, Tacoma, Washington, reenact restraint techniques in a pinhole camera workshop, 2002. Photo: Anonymous, courtesy of Steve Davis.

“Eradicating prisons in the US is part of a larger political awareness that folks must come to,” Pete explains. “As time goes on, I move away from the prison reformists who think prison can be fixed, towards the abolitionists who see the prison system as part of a patriarchal, sexist, racist, construct, which of course can’t be fixed, it needs to be dismantled. I don’t think the prisons can be fixed without society itself being fixed. I don’t think prisons can exist.”

“As a community we must truthfully tackle racism, misogyny, transphobia, homophobia, Islamophobia, all these things,” he continues. “Until all of those things are tackled fairly and wholly by us as a society then we can’t legitimately claim to be confronting the prison system, because prisons ultimately emerge from those same fears and white supremacy.”

“The Pryor Mountains. It is so special to me because I am from Pryor and I miss home. Castlerock at sunset.” Woman in Montana prison, from the series Supplication (2011-2013) Photo: Kristen S. Wilkins.

While individual photographers can’t bear the weight of that challenge alone, collectively photography can – and must – play a role in the fight for social justice. The work highlighted by Prison Photography, produced in the most restrictive circumstances and with the most voiceless people in American society, is proof of the immense value of photography in the search for truth (despite its limitations), representing what would otherwise remain unseen and ultimately creating the landscape for change.

Find out more about Prison Photography.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Clubbing is good for your health, according to neuroscientists

We Become One — A new documentary explores the positive effects that dance music and shared musical experiences can have on the human brain.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

In England’s rural north, skateboarding is femme

Zine scene — A new project from visual artist Juliet Klottrup, ‘Skate Like a Lass’, spotlights the FLINTA+ collectives who are redefining what it means to be a skater.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Donald Trump says that “everything is computer” – does he have a point?

Huck’s March dispatch — As AI creeps increasingly into our daily lives and our attention spans are lost to social media content, newsletter columnist Emma Garland unpicks the US President’s eyebrow-raising turn of phrase at a White House car show.

Written by: Emma Garland

How the ’70s radicalised the landscape of photography

The ’70s Lens — Half a century ago, visionary photographers including Nan Goldin, Joel Meyerowitz and Larry Sultan pushed the envelope of what was possible in image-making, blurring the boundaries between high and low art. A new exhibition revisits the era.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The inner-city riding club serving Newcastle’s youth

Stepney Western — Harry Lawson’s new experimental documentary sets up a Western film in the English North East, by focusing on a stables that also functions as a charity for disadvantaged young people.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The British intimacy of ‘the afters’

Not Going Home — In 1998, photographer Mischa Haller travelled to nightclubs just as their doors were shutting and dancers streamed out onto the streets, capturing the country’s partying youth in the early morning haze.

Written by: Ella Glossop