The dark, gritty underbelly of the post-Soviet east

- Text by Ellie Howard

- Photography by Petr Barabakaa

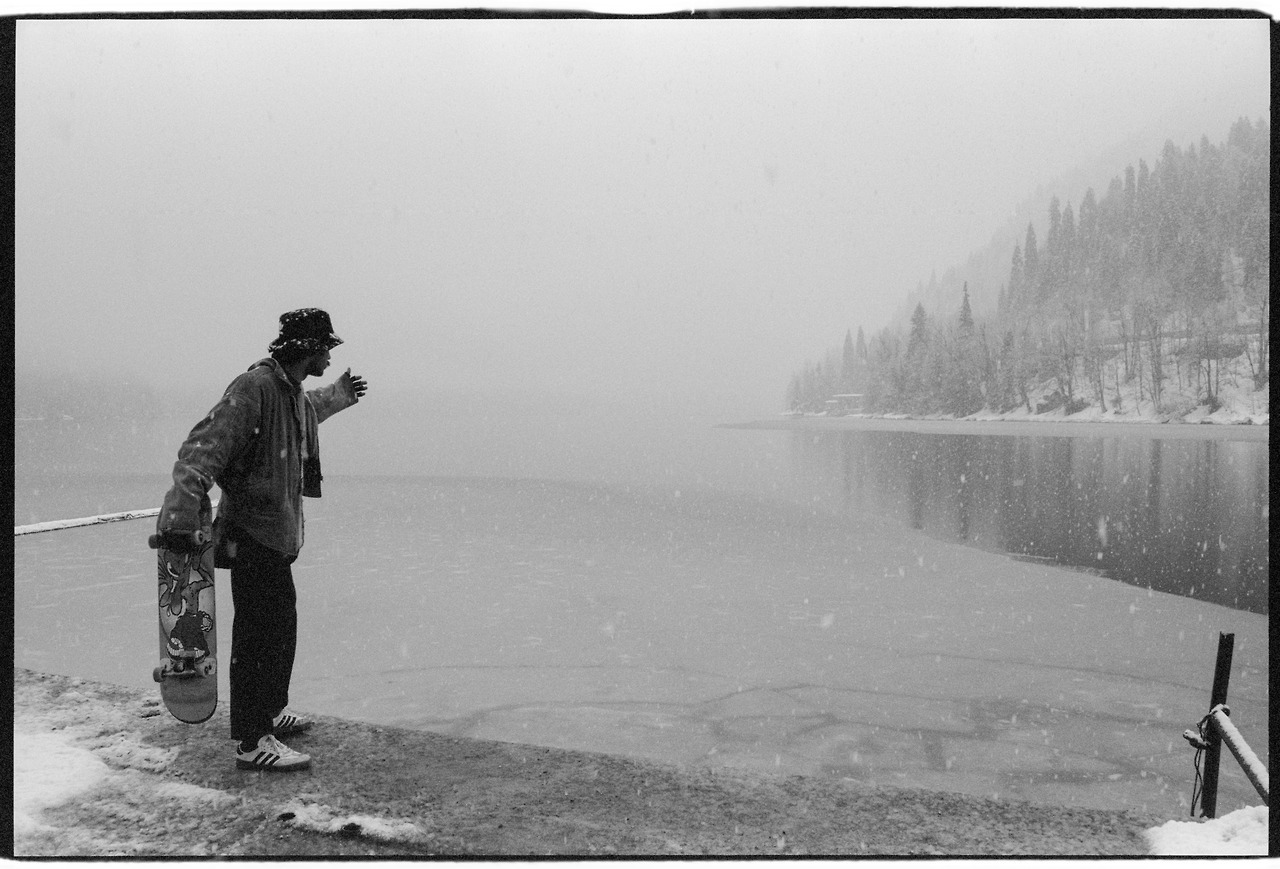

Petr Barabakaa found his first camera – a battered Kiev 19 SLR – in a skip. Ever since then, the Russian photographer has been making the streets his prime subject. Inheriting the visual vocabulary of USSR, his images burn with stark visual wit: Putin is parked next to Christ, kids point guns and skateboards slide amongst snow. However, his work has a separate agenda to the “Post-Soviet Youth” trend heralded by Russian luminaries such as Gosha Rubchinskiy. Barabakaa is only interested in revealing the dark, gritty underside of the New East.

A born and bred Muscovite, he tells me: “Moscow has gone through the craziest development in the last 20 years, even new neighborhoods are the size of separate cities.” A rapid urban expansion that’s mirrored the rise of skateboarding in Russia, with the sport blowing up over the past two decades.

“When you skate you are out on the streets. You speak a mutual language with the city,” he adds. “In some ways, it erases the fear of interacting with life. Skaters are impudent and self-confident. A lot of the time, you need these qualities for street photography as well.” Immediate, violent and with a slap of absurdism, Barabakaa’s images capture the streets as only a skater could: fleeting and accident prone.

You’re predominantly a skate photographer, but the skate scene in Moscow is still relatively young. Skateparks and outlets only appeared in the 90s. What has the scene evolved into today?

Despite Russian skateboarding being a young phenomenon, there had been a first big wave of skateboarding before I got into it. Most information about skateboarding came through American movies – when Russian skaters saw the look they realised that the boards they were skating at that moment were old fashioned. In 1989, even before the collapse of the USSR, Thrasher magazine did a skate trip to the Soviet Union. Back then, Russian skaters had very few proper skateboards that had been brought by foreigners, so they tried to copy them with help of ex-military factories. Production of proper skate wheels was the biggest issue.

The second wave of skateboarding came around 1998. That’s when I started skating. Before that, the scene was small and underground. Things changed when MTV started a Russian channel and a few good skate-related video games became big. Around the same time, Moscow got its first skate shops. But the real skate boom happened around 2003. We got local teams, videos, tours, websites, and magazines. It was really good until 2008, when the financial crisis hit Russia and the rate of our national currency went down badly. Recently, teenagers have switched from skate clothes and shoes to shopping malls and big sports brands. The industry suffered when a lot of skaters quit skateboarding for proper jobs. Skateboarding became expensive again.

Anyway, I hope for better. We need better economic conditions. For example, a good skateboard costs around 12000-15000₽ and an average payment around the country is 30000₽. Now you understand how hard it is for an average family to buy their kid a board.

Many of your portraits feature the homeless or those who suffer from addictions – characters similar to the ones shot by Miron Zownir or Boris Mikhailov. Has the problem of social care in Russia improved over the past 19 years?

It’s hard for me to decide. Boris shot his book in Kharkov, Ukraine in 1997 and Miron shot his book even earlier in 1995. Moscow in 1995 was very different from Moscow of 2017. Back then, I was very young and it’s hard for me to compare. I think that late ’80s and ’90s were the most interesting period for photography in modern Russian history. I collect books from that age and obviously, I have books by Miron and Boris in my collection. I think Moscow has become cleaner than it used to be. The ’90s were perfect for street photography. People were not scared of cameras and street action looked surreal. Nowadays, we have many charity organizations that help homeless people. Most of them are private but not state organized. Many volunteers care about homeless citizens. They feed them and organise warm spaces with showers and sleeping rooms. With 7-9 months of cold weather, being homeless in Russia is a lot different from being homeless in LA. You never know if you’ll survive the next winter.

Russia is going through quite a turbulent time politically and you often reinforce this with your imagery. How do you feel about the rise of Russian nationalism and does it feed into your work?

To be honest I don’t think there is too much turbulence here. It’s very stable, in the way that everything is controlled by security officials and they won’t hand power over anyone else. Vladimir Putin has been in power since 1999 and we have got a whole new generation of young people who are raising more questions than people from the USSR did. Still, the level of support of the current regime is very high. Propaganda does its thing very well. If you turn on Russian TV you will find yourself in a weird fairy tale that Russia is surrounded by enemies, but they just make us stronger. This message works for a lot of people. Concerning nationalism, I would call our current status aggressive patriotism that doesn’t really have a real base behind it. Most people don’t want to progress mentally and spiritually. People aren’t able to afford travel so judge the rest of the world from propaganda media sources. We need a young generation that has a wider view of the world. For the first step, you need to start to respect the person who is next to you. In modern Russia, a man is a wolf to another man.

You also do a lot of videography work, can you talk to me about your new film Absurd in Abkhazia?

Absurd is our big family. It’s a creative crew of people with skateboarding background. Next year, Absurd will turn 10 years old. We try to go to interesting countries and locations and skate there. Often, an interesting history of a place or its special status is the main motivation for us when we are looking for the next step. Abkhazia is an unrecognised country. It used to be part of Georgia during the USSR age, but when Georgia went independent in 1991 they tried to separate and create a national Abkhazian state. It all led to war. They came to a peace treaty in 1994, but Georgia still claims Abkhazia as one of its provinces but de facto Abkhazia is a separate country. Big international companies and banks are not allowed to do business in Abkhazia and it’s one of the reasons why it has stayed stuck in the past. It’s an absolutely unique place where incredible scenery borders with abandoned sanatoriums and resorts. We went to Abkhazia early spring with a small crew because we knew that there was almost nothing to skate. We were very unlucky with the weather and our Sony VX video camera got broken on the first day. We had to use pocket size Handycam instead. We could have been more productive but we will remember the trip for a long time.

You are very active in the Russian skate community, what other projects do you have going on at the moment?

I have less free time than I used too, so it’s hard for me to skate every day, but we are working on 10 years anniversary Absurd project. Even though there are certain positives in Russia skateboarding, I’m not interested in watching people skating in skate parks or jumping down stairs. I prefer creative side of skateboarding when skaters think of unusual architecture or interesting use of the urban environment. It’s something that makes European skateboarding special and I hope that we’ll also be able to catch up with European skaters at some point.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Is the UK ready for a Kabaddi boom?

Kabaddi, Kabaddi, Kabaddi — Watched by over 280 million in India, the breathless contact sport has repeatedly tried to grip British viewers. Ahead of the Kabaddi World Cup being held in Wolverhampton this month, Kyle MacNeill speaks to the gamechangers laying the groundwork for a grassroots scene.

Written by: Kyle MacNeill

One photographer’s search for her long lost father

Decades apart — Moving to Southern California as a young child, Diana Markosian’s family was torn apart. Finding him years later, her new photobook explores grief, loss and connection.

Written by: Miss Rosen

As DOGE stutters, all that remains is cringe

Department of Gargantuan Egos — With tensions splintering the American right and contemporary rap’s biggest feud continuing to make headlines, newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains how fragile male egos stand at the core of it all.

Written by: Emma Garland

Photo essay special: Despite pre-Carnival anxiety, Mardi Gras 2025 was a joyous release for New Orleans

A city celebrates — Following a horrific New Year’s Day terror attack and forecasts for extreme weather, the Louisiana city’s marquee celebration was pre-marked with doubt. But the festival found a city in a jubilant mood, with TBow Bowden there to capture it.

Written by: Isaac Muk

From his skating past to sculpting present, Arran Gregory revels in the organic

Sensing Earth Space — Having risen to prominence as an affiliate of Wayward Gallery and Slam City Skates, the shredder turned artist creates unique, temporal pieces out of earthly materials. Dorrell Merritt caught up with him to find out more about his creative process.

Written by: Dorrell Merritt

In Bristol, pub singers are keeping an age-old tradition alive

Ballads, backing tracks, beers — Bar closures, karaoke and jukeboxes have eroded a form of live music that was once an evening staple, but on the fringes of the southwest’s biggest city, a committed circuit remains.

Written by: Fred Dodgson