Musician Owen Brinley’s battle to overcome tinnitus

- Text by Owen Brinley

I can’t recall a time without tinnitus. Even as a child, if I listened carefully, I could hear its sustained notes. It never particularly bothered me, along with the drawn out moan of the nearby A1 (which I mistakenly thought to be the sound of clouds moving), it was just the way life sounded.

I’ve cultivated tinnitus ever since. Volume, from Marty McFly blowing up his Frankenstein guitar rig in Back to The Future to Nirvana practically deafening Jonathan Ross, was the coolest thing on earth. Like every other kid into music, I wanted in.

With the greasy sheen of teenage-dom, I finally got my own guitar rig to blow up… a family friend rewarding my burgeoning talent for the guitar with his unwanted tangerine-skin coloured 1970s Marshall Artiste amplifier. Teamed with my un-tuneable Epiphone 335 and cheap Zoom FX pedal, in my young mind I could now command a convincing impression of the rapturous noise of Oasis – Live By The Sea. A loud enough noise to warrant the police bashing on my window after school. I was in business.

It was soon time to see how all this was done properly, my first gig – Suede at York Barbican. After wasting £2 on the broken condom machine in Pizza Hut (bit ahead of myself there) and dressed in what I considered to be a convincing take on Britpop clothing – Kappa bottoms and a capped-sleeve Adidas T-shirt, I arrived to sheer derision from the black-clad goths assembled at the barrier. The fuckers obviously didn’t read Smash Hits.

Suede’s new guitarist Richard Oaks was a different kind of loud – trebly shards of smashed-glass loud. As my ribs grated against the metal barrier his Candy Apple Red Fender Jaguar lanced through the sweat and fag-ash air, slaying me from point black range. It was the most exciting sound I’d heard… and would be pretty much the last thing I did for the next week.

I awoke partially deaf, tinnitus now grappling for attention with everyday sounds. Perhaps for the first time a touch of panic set in. It was unpleasant and I wanted my old ears back, please.

Ignoring this little brush with hearing mortality, for the following decade I continued the quest to batter the living fuck out of my eardrums. At band practices, gigs, club nights and raves I’d hear wildly irritating frequencies screaming at me on fag-breaks from all the real noise inside. The noises inside my head couldn’t be escaped as easily – I’d developed two discordant frequencies a semi-tone apart. Achieving sleep became a nightly battle, bouts of anxiety and depression commonplace.

Looking back, this was all heading toward a logical conclusion. As a touring musician for much of my 20s, I’d begun to protect my ears with professionally moulded earplugs, thinking this would grant immunity from further damage. What I hadn’t realised was that protected or not – your ears need total breaks from noise to recover. I’d be rehearsing/recording all day and then gig, DJ or be drinking in clubs at night. I was fast-tracking toward a situation where tinnitus would be the least of my worries. I couldn’t stay away from music though, not for a minute.

I remember it very clearly – when everything changed completely and I would have totally re-evaluate my life. I’d been working on a Dept.M song called ‘J-Hop’, which perversely, was an audio-representation of all the ringing I suffered with. Maybe I was trying to inflict tinnitus upon the listener or express how tinnitus sounded within actual music. Really, it was a downright fucking harsh track but something about it excited me. With my headphones pumped I worked on the song relentlessly, only breaking to DJ or get a few hours broken sleep.

It was summer and I was covering a lot of my friend’s DJ shifts. After three consecutive nights out working I awoke to find my world had been put through a fucked Marshall stack. The screech of bus brakes sounded war-zone scary, the clink of glasses enough to make me jump and shudder. Even the sibilance of my girlfriend’s voice as we walked to the pub was unbearably cutting. It was like my life was broadcast through a WW1-era tannoy and it was called hyperacusis. Suddenly funny old tinnitus seemed a picnic by comparison.

Taking the worst possible action and researching it online, I found out all about my new friend, hyperacusis – a hearing condition characterized by an over-sensitivity to certain frequency and volume ranges (a collapsed tolerance to usual environmental sound). A person with severe hyperacusis has difficulty tolerating everyday noises, some of which may seem unpleasantly or painfully loud to that person but not to others.

There were no two ways about it, I completely fucking panicked. I quit my all DJing jobs and signed on, stopped making music and sat in silence waiting for my hearing to return to a semi-tolerable state. I read people’s comments on tinnitus and hyperacusis forums, some of which had totally retired from public life. They locked themselves in bedrooms and basements with earplugs in, as far away from any environmental noise as possible. From what I read there was no cure, just the damage done.

This time was an absolute nadir. Living with what I’d done to my hearing, perhaps my most valuable asset considering my love of music, was a bitter pill indeed. Social occasions were a real fucking wrestle, as I thought I needed earplugs in just to go to a bar. The only thing that would gift a few hours sweet relief and soften the edges was the stream of booze I’d pour myself every evening. Hangovers would somehow render hyperacusis even more potent though. You couldn’t bloody win.

Something had to give and I desperately searched for help. After the dour diagnosis of severe ear-fuckage from my GP, I was referred for regular testing in the ENT clinic at Harrogate hospital. My chink of light appeared in the shape of a wonderful woman who worked there. My tests returned normal hearing levels (looking back, unsurprising as my ears were so sensitive I could practically hear ants crawl) it was just the quality of hearing that was damaged. If I could still HEAR well, then maybe I could still make music, at least for a while. Sensing my sky-high anxiety levels she asked if I would return every other week for counselling sessions. These brilliant talks with her would prove to be an absolute saviour.

Through these sessions I started to come to terms with hyperacusis. Music was everything and I learned things that resurrected my chances of living an enjoyable life again. I didn’t have to and shouldn’t quit music – as long as I wasn’t stupid (again) and rested my ears afterwards. I learned that although my ears were showing signs of damage they wouldn’t deteriorate any further or faster than anyone else’s. I was reassured enough to start channelling my energy into putting a new band together, rather than spending my life typing on tinnitus forums.

I started to realise that many issues with tinnitus and hyperacusis are focus-based. You give too much attention to the issue and sure enough the screaming and sensitivity is there. At the onset of hyperacusis, I was living life bracing myself for the next sound, like waiting for a punch in the gut. Sure enough, it hurts if you’re waiting for it.

Playing music again was scary but ultimately the most therapeutic thing I could’ve done. I still wear industrial ear-defenders (on top of earplugs) to play live, otherwise the sound is just too loud for my ears to fully comprehend. Although I sometimes feel embarrassed to wear them, it’s nothing really, I’m just relieved I can still play. Maybe one day I’ll manage a step further and lose the defenders.

From the low of what I thought was game-over, the proceeding years have actually seen my hearing problems gently ease over time. In my case (and I’d wager a lot of others) it’s the attention and anxiety you focus on the problem that actually fuel it.

Something to bear in mind – if you pay tinnitus little attention and get on with things, the brain gets bored of listening to it and tunes out over time. I still hear my tinnitus every day but to say I now ‘suffer’ with it would be an overstatement. Hyperacusis, is a whole other fresh hell but again, over time you can get the measure of the fucker. I now work in an office above a factory floor of industrial band-saws and heavy artillery. Walking through the factory is difficult but that I’m able to do so would have been utterly unthinkable a couple of years ago.

If you’re really suffering, don’t panic and cut yourself off from others. Protect your hearing from further damage as a matter of urgency – ACS Pro-moulded earplugs are an essential. On a final note, God bless the NHS.

Department M’s new single Bleak Technique is out now on Hide & Seek Records. Catch them live at a free gig at Birthdays, Dalston on October 10.

Latest on Huck

In the ’60s and ’70s, Greenwich Village was the musical heart of New York

Talkin’ Greenwich Village — Author David Browne’s new book takes readers into the neighbourhood’s creative heyday, where a generation of artists and poets including Bob Dylan, Billie Holliday and Dave Van Ronk cut their teeth.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

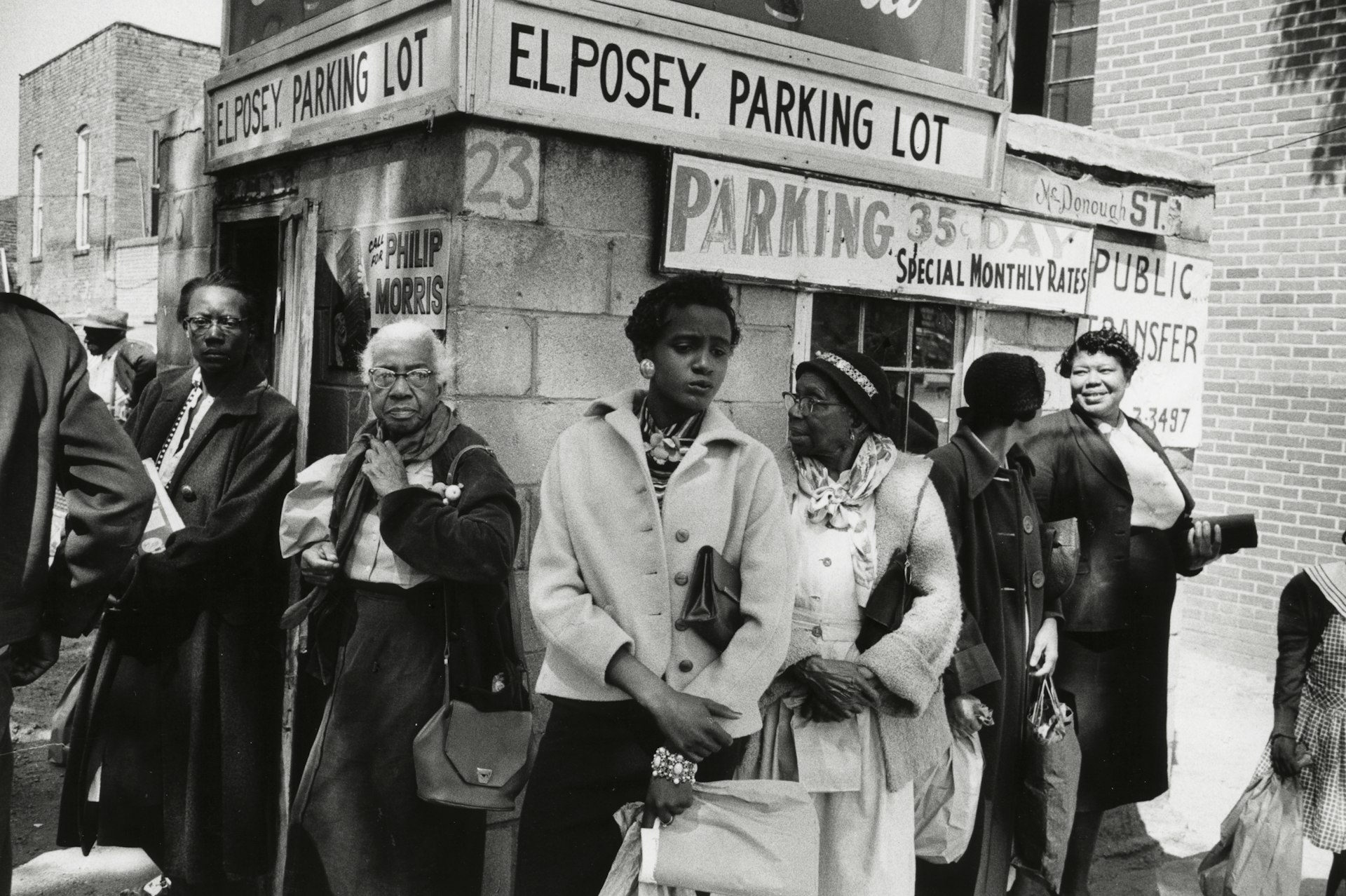

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk