The movie star who doubled as a groundbreaking inventor

- Text by Daniel Dylan Wray

Whenever Hedy Lamarr used to come home after a long day on set, she’d stay up all night. Back in the 1940s, actors would retire to bed with a studio-issued sleeping pill – knocking them out before an ‘upper’ brought them back around.

But Hedy Lamarr was different. She’d hover over her drafting table by lamplight, toying with test tubes or filling notebooks with ideas. “Any girl can be glamorous,” Hedy once said. “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

Yet over the course of an extraordinary career, Hedy was less known for her groundbreaking research and more for a life of controversy. It began when she starred in the first mainstream film to show sexual intercourse and a female orgasm, 1933’s Ecstasy.

A scandal erupted and, after a failed marriage, the actress fled Nazi Germany, desperate to start over. Still going by her birth name Hedwig Kiesler, she plotted her way onto the roster of MGM studio mogul Louis B. Mayer, who rebranded her in the US as “Hedy Lamarr: the world’s most beautiful woman.”

But life as a Hollywood star took its toll and Hedy’s twilight years were spent as a recluse in Miami. It’s a legacy so complex that just retelling it – let alone forming a clear picture of who Hedy really was – becomes fraught with difficulty. “It wasn’t her beauty and it wasn’t her brains,” says director Alexandra Dean, recalling what inspired her to make Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story. “It was her bravery, how bold she was.”

The documentary follows Hedy’s quest to use her star status as a platform to get ideas heard. After dating billionaire Howard Hughes, she harnessed his resources to develop her own engineering concepts (like improving traffic stop lights) while helping out on some of his (like how to get planes to fly faster).

A self-taught inventor, Lamarr studied up on birds and fish, then drew an aerodynamic design that combined both of their features. “You’re a genius,” was Hughes’ response. “She just had this wonderful mind that knew how to design a better airplane wing,” Alexandra says now. “Can you imagine having the self-confidence to do that? It’s inspiring.”

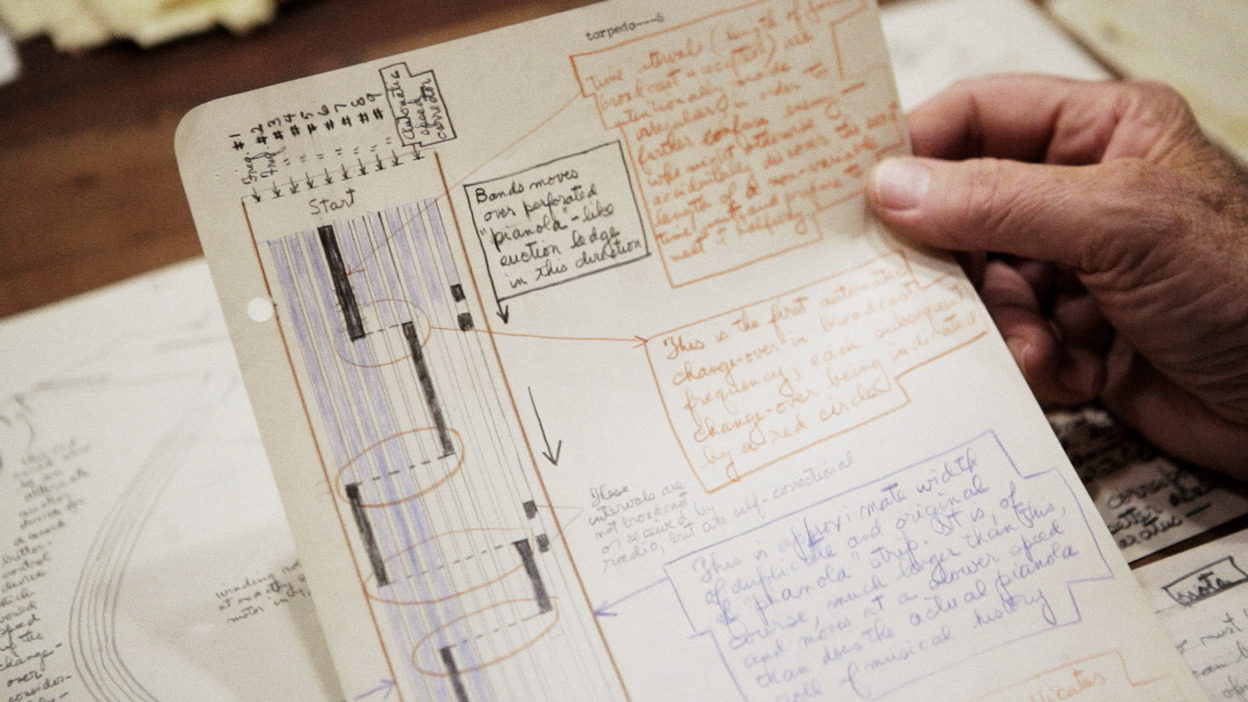

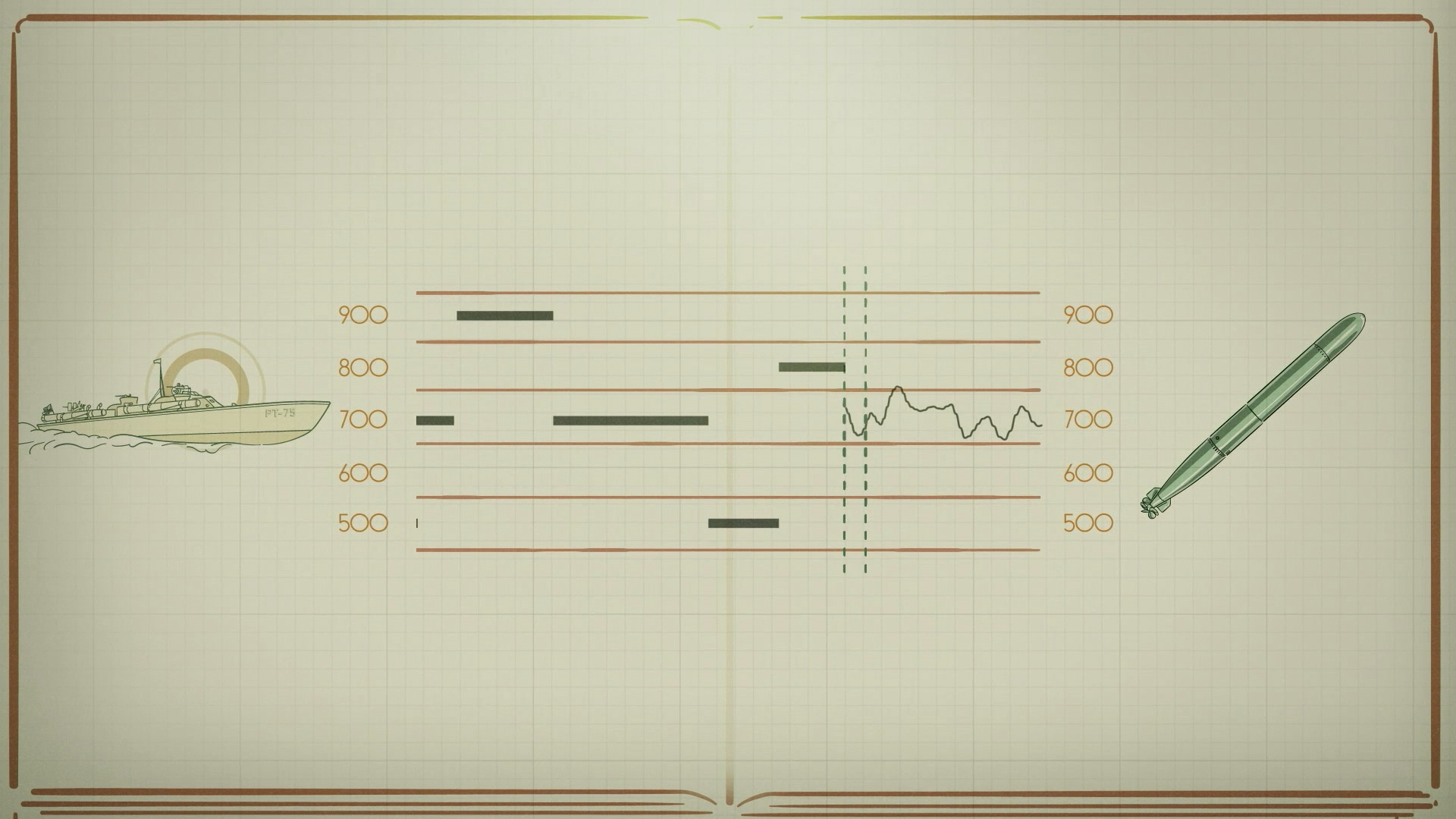

Hedy’s most significant invention was one she worked on with the avant-garde composer George Antheil. The pair wanted to help the Allied cause during WWII, so they began designing a radio guidance system that allowed torpedos to avoid enemy detection. Ultimately it was rejected by the Navy and Hedy was told that she’d be more helpful as a fundraiser, using her celebrity status to sell war bonds and entertain troops.

But after raising millions of dollars doing exactly that, her patent was seized when she was deemed an alien due to her Austrian nationality. Twenty years later, with her name removed from the invention, her technology was put to use during the Cuban Missile Crisis. “Sons of bitches!” Mel Brooks howls when he learns of this in the film.

Those very same principles are now a core component of Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, GPS and various military technology – an invention with an estimated market value of $30bn. To make matters worse, it’s been disputed that Hedy came up with the idea at all, with some believing she stole it from the Nazis and hid it in her shoe – an assertion Bombshell proves false.

But the film isn’t just about an uncredited inventor. It’s about a woman who had a paradoxical relationship to her appearance, which opened doors but stopped her from being taken seriously. “I think of her as a superhero,” Alexandra says. “She just wouldn’t accept what people said about her beauty. She would let it give her this incredible power, let it propel her forward into these elite worlds, and then use her brains.”

As Hedy grew older, that became more difficult. She got hooked on methamphetamines, believing she was taking B12 injections, which made her behave erratically. She also became estranged from her family, was arrested for shoplifting and underwent a series of botched plastic surgeries. The press, meanwhile, depicted this as a sensational fall from grace.

“She spent her whole life telling people, ‘Don’t judge me on my face’, and then the minute she starts to lose her beauty, it’s as if she flips over and has to acknowledge how much power it’s given her,” says Alexandra. “Then she tries to fix the problem and loses her superpowers. She loses her conviction that she is so much more than that face.”

Back then, the director explains, Hollywood was a brutal machine that treated contracted actors like slaves. “It was so difficult to endure psychologically that, when you consider how many drugs actors were asked to take on top of that, they didn’t stand a chance.”

But rather than view Hedy’s life as a tale of lost potential, Alexandra feels it makes her accomplishments all the more remarkable. “Hedy really was so strikingly brave that she never accepted any of the constraints that the world was trying to put around her. She was a true escape artist.”

Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story is in cinemas and available on-demand from 9 March.

This article appears in Huck 64 – The Journeys Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Latest on Huck

Amid tensions in Eastern Europe, young Latvians are reviving their country’s folk rhythms

Spaces Between the Beats — The Baltic nation’s ancient melodies have long been a symbol of resistance, but as Russia’s war with Ukraine rages on, new generations of singers and dancers are taking them to the mainstream.

Written by: Jack Styler

Uwade: “I was determined to transcend popular opinion”

What Made Me — In this series, we ask artists and rebels about the about the forces and experiences that shaped who they are. Today, it’s Nigerian-born, South Carolina-raised indie-soul singer Uwade.

Written by: Uwade

Inside the obscured, closeted habitats of Britain’s exotic pets

“I have a few animals...” — For his new series, photographer Jonty Clark went behind closed doors to meet rare animal owners, finding ethical grey areas and close bonds.

Written by: Hannah Bentley

Frazer Clarke: “I had a hole in my leg, I’m very lucky to be alive”

Hard Feelings — For our interview column on masculinity and fatherhood, the Olympic boxing medallist speaks to Robert Kazandjian about hard graft, the fear and triumph of his first fight, and returning to the ring after being stabbed on a night out.

Written by: Robert Kazandjian

Remembering Holly Woodlawn, Andy Warhol muse and trans trailblazer

Love You Madly — A new book explores the actress’s rollercoaster life and story, who helped inspire Lou Reed’s ‘Walk on the Wild Side’.

Written by: Miss Rosen

This photographer picked up 1,000 weed baggies in New York and documented them

0.125OZ — Since originally stumbling across a discarded bag in Brooklyn, Vincent ”Streetadelic” Pflieger has amassed a huge archive of marijuana packaging, while inadvertently capturing a moment as cannabis went from an illicit, underground drug to big business.

Written by: Isaac Muk