Uncovering the world’s largest collection of drug ephemera

- Text by Alex Robert Ross

- Photography by Altered States / Anthology Editions

One of the first objects that Peter Watts writes about in his new book, Altered States: The Library of Julio Santo Domingo, is an embalmed grapefruit. Keith Richards had used it instead of wrapping paper when he gave Ronnie Wood a ring for his birthday, on tour in Munich in 1990. He stuffed the ring inside the grapefruit and wrote “Happy Birthday Ron” on the skin in black marker. Wood picked out the gift and discarded the grapefruit in his hotel room’s trash can, as anyone might.

But Julio Santo Domingo, a friend of the band, needed that grapefruit. It was a piece of history. It needed to be preserved. He stole the trash can, took the grapefruit back with him to his home in Geneva, stuck it in his fridge, and then set about trying to find someone who would mummify it for him. Eventually, the job fell to a taxidermist in Austria. “Julio loved it,” Watts writes. “To him, something shed from the trash was as important as a first-edition Thomas De Quincey.”

Santo Domingo was a compulsive collector of drug-related literature, paraphernalia, and ephemera. Born into money in 1958, the son of a wealthy Colombian magnate, he didn’t care much for the boardroom as a kid. He lionised the beat poets and their European predecessors, hallucinogen-inspired libertines and dropouts. He moved to New York in the late ‘70s and studied at Columbia University. By the early ‘80s, when Santo Domingo was still in his early 20s, the compulsion to collect had set in. He’d keep hold of things that anyone else might discard, all for posterity. He was, as his wife Vera tells Watts in Altered States, “keeping his whole life in time capsules.”

Julio Santo Domingo and David Bowie. Photographer Johnny Pigozzi. From Altered States, published by Anthology Editions.

From Altered States, published by Anthology Editions.

His collection soon took serious shape. He first obsessed over the Rolling Stones. (His godfather, Ahmet Ertegun, was the head of Atlantic Records, so access wasn’t a problem). He did everything in his power to get hold of rare Stones items, the type of things that the average obsessive wouldn’t even think of, all the way down to that grapefruit.

But the Stones were just the gateway. They were, Watts writes, “a natural fit for Julio, living the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll lifestyle, hanging out with Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, working with Andy Warhol and referencing the likes of Charles Baudelaire and Aleister Crowley.” In the late 90s, when Vera suggested that he find a more serious focus for his impulse to accumulate, he immediately decided to focus on drugs.

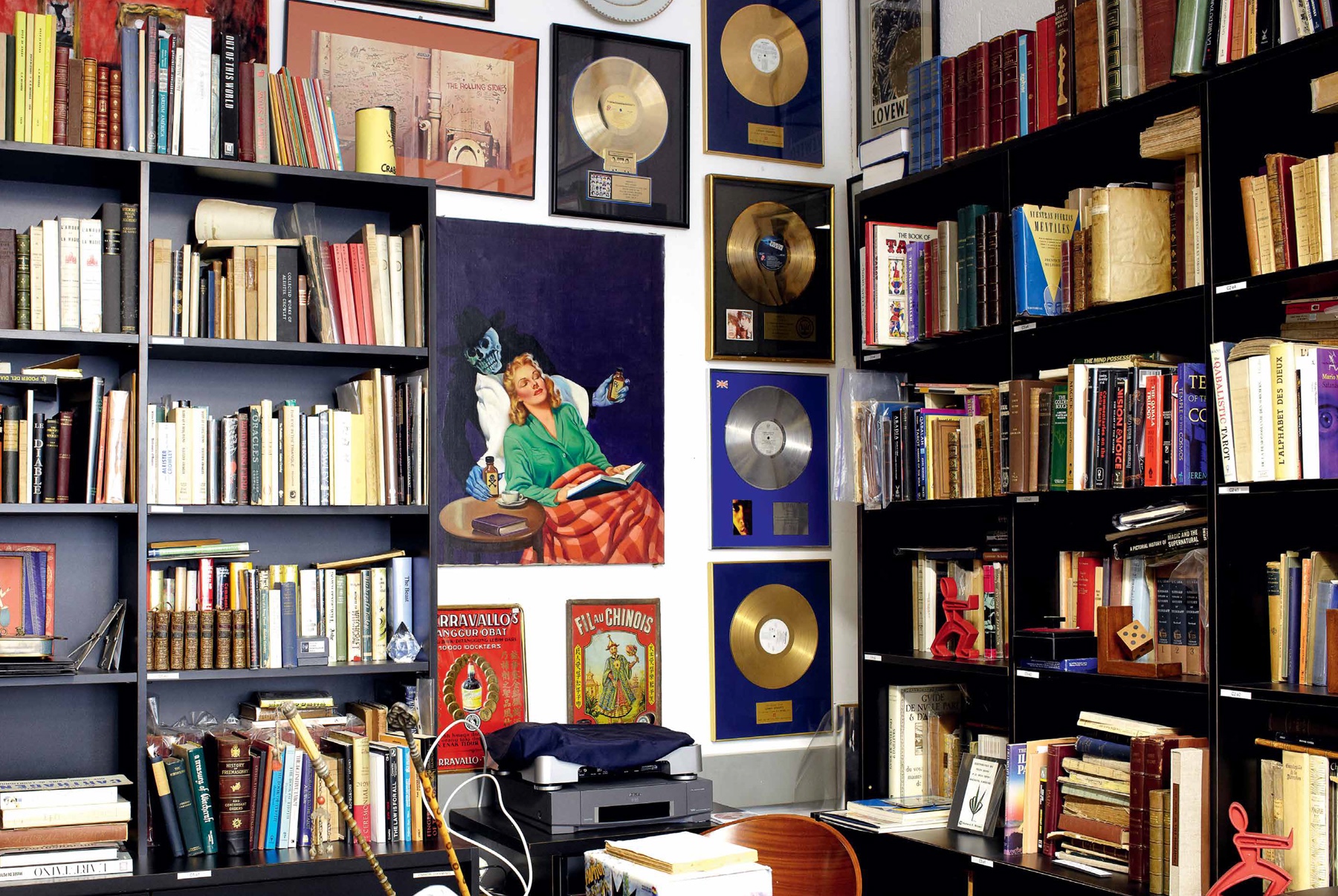

The sprawling collection that Watts details in Altered States – subject by subject, piece by piece, over almost 500 beautifully designed pages – moved to Harvard University in 2012, three years after Santo Domingo’s death. But the bulk of the LSD Library, as the collector christened it, was originally homed in the Swiss town of Thônex. It covers everything from cocaine to opium to weed, black magick to beat poetry, erotica to romanticism. Anything that might have alluded to drugs and their effects, even briefly, was there in Geneva. An old copy of National Geographic, for example, sat in the corner, “because of one paragraph of one story that references the “dream fish” (Kyphosus fuscus), a psychotropic/hallucinogenic fish found in the waters off Norfolk Island in the Pacific, which is said to give people strange dreams after they have eaten it.”

From Altered States, published by Anthology Editions.

From Altered States, published by Anthology Editions.

The collection, Watts says over the phone from his home in London, “took over three huge rooms, each the size of a terraced house,” he says. “There were things that just didn’t make sense. It wasn’t just lots of books. There were medicine bottles, there were posters, and there were plastic marijuana leaves and some things that you’d consider really tacky. The sort of things they’d sell in Camden market, alongside a book by Baudelaire.”

In Altered States, Watts writes about how difficult it was to figure out a connection between seemingly random objects: “You would find everything from the sublime – a handwritten note by Thomas De Quincey complaining of an opium-related illness – to the ridiculous: a doll of Dopey, the stoned dwarf from Snow White.”

He doesn’t dwell on it in the book, but that Dopey doll was the key that unlocked Julio’s strange process. He found it in the second of those three huge rooms. “And it just suddenly made sense, the humour behind it. I’d never really thought of Dopey the Dwarf as being stoned, but in that context, yes, of course he was stoned. I had to think like Julio as much as I could, which is quite abstract. It’s not just obviously drug things. It’s everything that may have been vaguely touched by drugs or altered states.”

From Altered States, published by Anthology Editions.

Julio Santo Domingo. From Altered States, published by Anthology Editions.

So Watts finds coherence in the chaos by treating each object as Santo Domingo did. He’s fascinated by a first edition of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, signed by Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Herbert Huncke. But he devotes just as much space to a cheap, plastic MacDonald’s coffee spoon from 1980. The company had redesigned it that year, filling in the head to discourage people from using it as a coke spoon. It is, Watts writes, a “fascinating piece of ephemera, which says a considerable amount about drug- use politics and economics of the era. It is difficult to imagine that any other collector would conceive including it in their collection.”

Watts insists that there aren’t many obvious parallels between Santo Domingo’s compulsion and the author’s obsessive tendencies. “If I’m speaking personally, I’m quite tidy,” he says. But after immersing himself in Santo Domingo’s world, he understands the collector’s urge. In the introduction to Altered States, he quotes Phillipp Blom: “the most important object in any collection is always the next one.”

“That really was a brilliant distillation of that kind of compulsive collecting behaviour,” Watts says. “You’re never going to be satisfied. You’re always going to want the next one, because that’s the joy of it.”

Altered States: The Library of Julio Santo Domingo will be released by Anthology Editions on December 5.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

From his skating past to sculpting present, Arran Gregory revels in the organic

Sensing Earth Space — Having risen to prominence as an affiliate of Wayward Gallery and Slam City Skates, the shredder turned artist creates unique, temporal pieces out of earthly materials. Dorrell Merritt caught up with him to find out more about his creative process.

Written by: Dorrell Merritt

In Bristol, pub singers are keeping an age-old tradition alive

Ballads, backing tracks, beers — Bar closures, karaoke and jukeboxes have eroded a form of live music that was once an evening staple, but on the fringes of the southwest’s biggest city, a committed circuit remains.

Written by: Fred Dodgson

This new photobook celebrates the long history of queer photography

Calling the Shots — Curated by Zorian Clayton, it features the work of several groundbreaking artists including Robert Mapplethorpe, Sunil Gupta, Zanele Muholi and more.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Krept & Konan: “Being tough is indoctrinated into us”

Daddy Issues — In the latest from our interview column exploring fatherhood and masculinity, UK rap’s most successful double act reflect on loss, being vulnerable in their music, and how having a daughter has got Krept doing things he’d never have imagined.

Written by: Robert Kazandjian

Vibrant polaroids of New York’s ’80s party scene

Camera Girl — After stumbling across a newspaper advert in 1980, Sharon Smith became one of the city’s most prolific nightlife photographers. Her new book revisits the array of stars and characters who frequented its most legendary clubs.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Bad Bunny: “People don’t know basic things about our country”

Reggaeton & Resistance — Topping the charts to kick off 2025, the Latin superstar is using his platform and music to spotlight the Puerto Rican cause on the global stage.

Written by: Catherine Jones