David Shrigley: Life lessons from an art world anarchist

- Text by Adam White

- Photography by Victor Frankowski

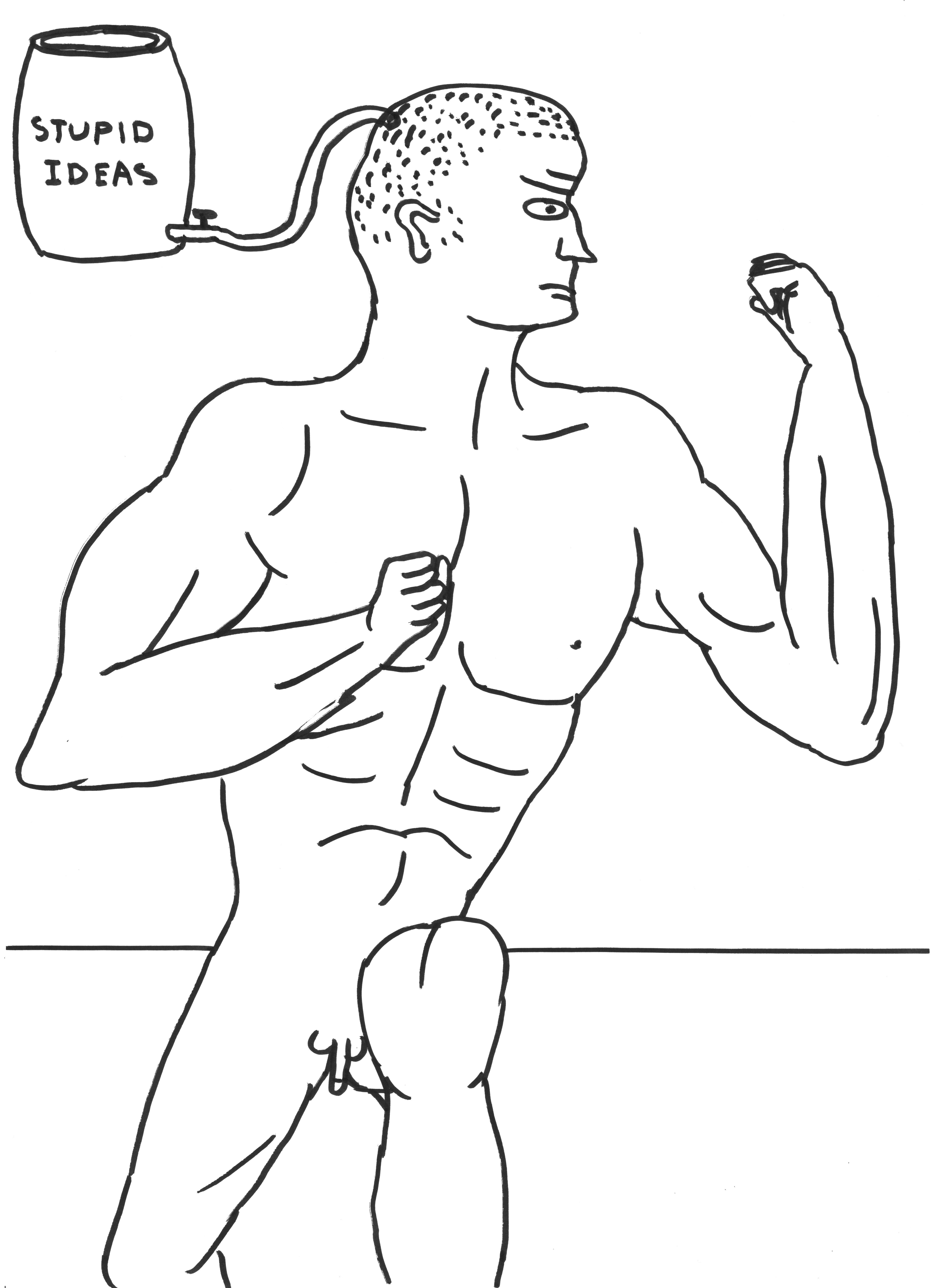

David Shrigley has drawn incarnations of comedic nihilism for over 25 years, his most famous works made up of scribbles, rough sketches and small, surreal bursts of wit. To many, they speak to universal mores, or largely unspoken melancholy. To others, they don’t look like much at all.

“I feel like I’ve become famous for picking my nose,” he explains over the phone from his home in Brighton, where he is guest directing this year’s Brighton Festival. “But somehow somebody saw me picking my nose and thought, ‘Ah, that’s cool! Nobody else picks their nose like you do!’ Obviously, I’m joking… but it feels a bit like that.”

The artist understands if people roll their eyes at his success. He recalls times when he’s told strangers what he does for a living, immediately impressing them by nature of his profession, only to see their smiles drop when they actually Google his work.

“You kind of see them later at the party or whatever and they’re on their phone and you can see the look on their face like, ‘Fucking hell, he’s famous for doing that?’” Shrigley says with a laugh. “‘It’s just rubbish!’”

Has it been tough knowing that your art is that divisive? “You have to make the work satisfy yourself,” he says, practically. “Other people’s opinions are important, but you can’t make work for other people, or with other people in mind. It just doesn’t work… Ultimately you’ll end up making art for nobody, and then nobody will like it. Whereas if you just make it for yourself, at least you’re guaranteed that one person’s gonna like it.”

Shrigley’s art first found fans in the mid-90s, where his frank, funny tributes to futility and despair somehow struck a chord, even in the optimistic climate of Britpop and New Labour. But while many of his contemporaries have fallen out of favour in the years since, Shrigley’s work remains culturally ubiquitous. Even more unexpectedly, his observations feel directly attuned to the humour of today.

In the past decade, deadpan self-awareness – reading either endearingly defiant or vaguely deranged – has almost become the language of the internet, particularly when channelled through memes. Shrigley may not have created Evil Kermit or the FBI agent monitoring you via your webcam, but it all feels undeniably Shriglian.

Though he isn’t a big user of social media himself, Shrigley says that he notices similarities between his work and social media parlance. “I deliberately seek to make work that delivers messages that arrive de-contextualised, [because] that’s where the oblique comedy comes from,” he explains. “It’s the same with social media, tweets or Instagram posts – they arrive de-contextualised… and seem oblique and strange and mordant. They just refer to something very, very specific or don’t refer to anything, and they become re-contextualised by the person who reads them.

“I’m always interested in comedy that is really oblique and apropos of nothing. That’s my thing – and maybe that’s the internet’s thing as well.”

Despite the similarities, Shrigley’s art came of age pre-internet. Raised by Christian fundamentalist parents in Leicester, Shrigley grew up drawing in sketchbooks and notepads, before attending the Glasgow School of Art. He studied Fine Art, but his interest in drawing comedic works, often devoid of much formal craft, made him an outlier among his peers. He credits his tutors for always supporting his vision, even if they didn’t quite get it, but admits he left art school in 1991 with “a 2:2 and a chip on [his] shoulder”.

The work found an audience, though. Encouraged by friends, Shrigley began to market his drawings via self-published books, photocopying a hundred copies at a time of his acerbic, sneakily satirical sketches. By 1995, he had become a cult figure among the Young British Artists contingent, and landed the cover of Frieze.

Today his scribbles decorate tea towels and stationary, mugs and inspirational posters. It’s also the rare sort of art to cross over into everyday visibility, finding fans among both art gallery connoisseurs and your Susans from Accounting. Such relatability has made Shrigley one of the most financially successful artists of his generation, but it’s also created something of a gulf between him and the art itself. What was once an oddball pursuit has, for better or worse, become public property.

“I find that as I’ve got older, I’ve become more and more detached from it,” he says. “I see the work as something that I’m somehow a custodian of rather than the creator of. I don’t know if that suggests I may be mentally ill. But I feel as if the work is sort of growing in a garden, and I just sort of harvest it and present it to the world.”

He’s more interested in how reactions to his art shift depending on the context they’re placed in, whether it’s in a gallery or on a T-shirt. He cites “Really Good,” his bronze sculpture of a thumbs up that currently sits atop the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, as an example.

“People’s responses to it are not about whether it’s good or bad, it’s about people taking selfies and events happening around it and the context changing,” he explains. “The work’s a proposition and people are responding to that proposition and then making other propositions to you. It’s really fascinating, and that’s the virtue of the situation that I find myself in.”

It’s a situation that Shrigley is thoughtful of. He notes his privilege as an artist who, thanks to the success of his sketches, doesn’t necessarily need to work on things he has no interest in.

Since he came to fame, Shrigley has directed music videos, dabbled in advertising, composed operas, worked as a DJ and experimented with sculpture, photography and fashion design. It’s a creative drive devoid of boundaries, and something Shrigley encourages young artists of today to try and emulate for themselves.

“Don’t be afraid of failure,” he says. “Examine all the variables, do something different, go down a path until it appears boring, and then change.”

David Shrigley is the Guest Director of this year’s Brighton Festival, which runs from May 5 – May 27. His new book Fully Coherent Plan is out via Canongate on 3 May.

Follow Adam White on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Led By Donkeys: “It’s weird when right-wing commentators get outraged by left politics at Glastonbury – what did they expect?”

Send them to Mars — With their installation in Block9 launching the billionaire class into space, we caught up with the art and activism crew to chat about the long intersection of music and politics at the festival, how wrong the tech bros are, and more.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How pop music introduced queer culture to the mainstream

The Secret Public — Between the ’50s to the ’70s, pop music was populated with scene pushers from the margins. A new book by Jon Savage explores the powerful influence of LGBTQ+ folk.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The Getty Center’s first exclusively queer exhibition opens today

$3 Bill: Evidence of Queer Lives — Running until September, it features paintings, ephemera, video and photography to highlight LGBTQ+ histories, culture and people from 1900 to the present day.

Written by: Isaac Muk

A new documentary explores Japan’s radical post-war photography and arts scene

Avant-Garde Pioneers — Focusing on the likes of Daidō Moriyama, Nobuyoshi Araki, Eikoh Hosoe and many more, the film highlights the swell of creativity in the ’60s, at a time of huge economic change coupled with cultural tensions.

Written by: Isaac Muk

From his skating past to sculpting present, Arran Gregory revels in the organic

Sensing Earth Space — Having risen to prominence as an affiliate of Wayward Gallery and Slam City Skates, the shredder turned artist creates unique, temporal pieces out of earthly materials. Dorrell Merritt caught up with him to find out more about his creative process.

Written by: Dorrell Merritt

Inside the world’s only inhabited art gallery

The MAAM Metropoliz — Since gaining official acceptance, a former salami factory turned art squat has become a fully-fledged museum. Its existence has provided secure housing to a community who would have struggled to find it otherwise.

Written by: Gaia Neiman