Letizia Battaglia: the Sicilian woman who shot the mafia

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Letizia Battaglia

“I wasn’t a real person [before I picked up the camera],” says Sicilian photographer Letizia Battaglia in the powerful new documentary, Shooting the Mafia.

Battaglia took up photography at the age of 36, and eventually got a job working for L’Ora newspaper. Liberated from the constraints of patriarchy, which had stunted the full formation of her identity and agency until then, the position helped her come into her own.

When Battalia was just 10 years old, a man masturbated in front of her on a Palermo street. In retaliation, her father locked her away inside the house, refusing to allow her on the balcony in case another man should see her. She was then sent to a Catholic school, which turned her into an atheist. In rebellion, at 16, Battalia married the first man who asked her and bore him three daughters.

Her husband, like her father, denied Battaglia the freedom she craved and she eventually had to be hospitalised after having a mental breakdown. She spent two years in Switzerland recovering, returned to Sicily where she began to take lovers – one of whom was shot when her husband discovered them in bed together.

Shortly after, she got a divorce, and became the first Italian woman photographer at a daily newspaper. Three days into the job, she saw her first murder. “It never leaves you,” Battaglia says in the film.

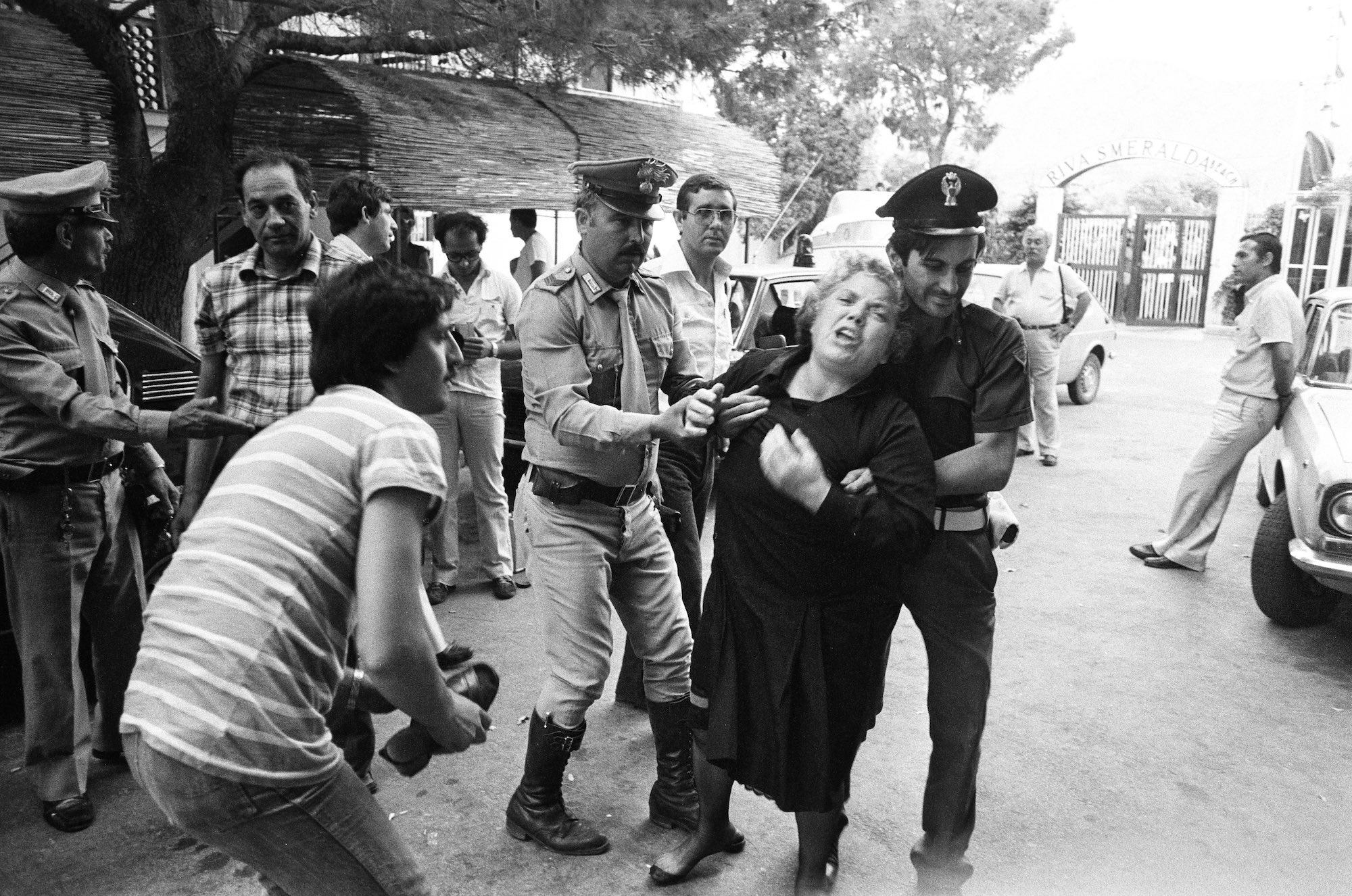

Over the next two decades, Battaglia photographed the victims of the mafia, boldly going so far as to show her work in Corleone, a small Sicilian farming town and home to one of the most powerful families, in order to directly challenge omerta, the mafia’s code of silence.

Battaglia received death threats. Her camera was smashed. But the mafia let her live. “Letizia’s photos were always on the front page of the newspaper and kept the killings in the minds of the people, particularly the magistrates,” says Kim Longinotto, the film director. “They are making the community look at what is happening. They are powerful threats against speaking out.”

Battaglia’s photographs humanised the victims, revealing how cowardly the mafia was for murdering trade unionists, women, and children – as well as judges who were being targeted for investigating organised crime.

At the same time, her photographs were of fearsome things. Devoid of Hollywood glamour and glitz, they were pictures taken inside a war zone. Rather than heroicise the killers, Battaglia cared about the dead, as well as those forced to live through violence and trauma. Shooting the Mafia reveals Battaglia courage and dedication to the people of her native land, while chronicling the mafia’s brutal reign over Sicily during the twentieth century.

After 20 years, Battaglia stopped taking photographs. One of her last photos shows a young boy who was shot in the back of his head after seeing his father murdered. “It was never the same,” she says in the film. “You can never be happy after that kind of horror.”

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Jake Hanrahan: “Boys can cry, but we don’t all fucking want to”

Hard Feelings — In the latest edition of our column on masculinity and fatherhood, Rob Kazandjian speaks to the conflict filmmaker-journalist and Popular Front founder about his childhood, the found family and community at his Muay Thai gym, and the “complete counterculture” of ‘no rules’ fighting.

Written by: Robert Kazandjian

Euphoric portraits of queer joy and resistance at Trans Pride Brighton

Let us piss — Now over a decade old, the event grew to become Europe’s largest trans pride march. In a year when trans rights have come under the microscope more than ever, we went to this year’s edition, finding grassroots unity and collective rage.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Remembering the radical anti-nuclear Greenham Women’s Peace Camp

Life at the Fence — In the early ’80s, a women’s only camp at an RAF site in Berkshire was formed to protest the threat of nuclear arms. Janine Wiedel’s new photobook revisits its anti-establishment setup and people.

Written by: Miss Rosen

A new documentary traces the rise, fall and cratering of VICE

VICE is broke — Streaming on MUBI, it’s presented by chef and filmmaker Eddie Huang, who previously hosted travel and food show Huang’s World for the millennial media giant.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Warm, tender photos of London’s amateur boxing scene

Where The Fire Went — Sana Badri’s new photobook captures the wider support networks and community spirit around the grassroots sport, as well as the significance of its competitions to the athletes who take part.

Written by: Isaac Muk

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro