Five things you need to know about culturehacking

For New Zealand artist Simon Denny, the treasure trove of government intelligence files leaked by Edward Snowden sparked a peculiar obsession. After being struck by the quality of the NSA’s artwork and internal branding, Denny zeroed in on David Darchicourt, NSA creative director from 2001-12 – a position few knew about previously.

Denny helped reveal the imagery secretly produced by the NSA to the world through using it in his own artistic work. Then he trolled Darchicourt into unknowingly producing work for Denny’s own show at the Venice Biennale in 2015.

Denny is one of a growing number of artists and activists using culturehacking to break into the institutions that dominate our lives; overtly, like government spy agencies or implicitly, like tech giants Apple and Google. Culturehacking can be a powerful tool to understand the internal cultures that drive these organisations in order to challenge them, subvert their authority – or just laugh at them.

To coincide with Denny’s Products for Organising show at Serpentine Sackler Galleries, he joined a panel discussion at the Royal College of Art alongside three other notorious culturehackers: including Homeland hacker and artist, Heba Amin, gonzo financial anthropologist and author of The Heretic’s Guide to Global Finance, Brett Scott and The Intercept journalist and Snowden files investigator, Ryan Gallagher. Together, they explored various interpretations of culturehacking and how the concept applies to their own work.

Huck went along, listened up and got schooled. Here are the five most important things we learned.

1. Why culturehack?

Is there anything inherently good about messing with things? Or, as was discussed at the panel, should we leave stable structures alone for fear of making things worse – even if they are flawed or corrupt, as in the case of the case of Arab Spring or Euromaidan demonstrations in Ukraine, which, arguably, made bad situations worse?

“The last few years of my life have been devoted to going through the Snowden documents to write stories about them and I guess that’s messing with the spy community and powerful government structures,” Ryan explains. “So, what comes out of that?”

The Snowden revelations have failed to lead to significant reforms on either side of the Atlantic. “[In the UK] the government has doubled down and tried to do more extreme spying, even though it’s already doing some of the most extreme spying in the world,” Ryan explains

Yet, Ryan still sees important changes provoked by the secret information he and Snowden have disseminated. “I think what is important is the cultural awareness of people, this collective consciousness – if you want to call it that,” Ryan explains. He’s watched with pleasure how the Snowden revelations have seeped into popular culture, such as The X-Files and prompted huge tech companies like WhatsApp to implement anti-government encryption. “It just changes people’s awareness, I think in some ways it’s changed the behaviour of people,” he explains. “For me, what comes out of messing with big government structures and doing this kind of reporting, is that it informs people and can slowly drive us towards cultural evolution – how we behave as a society.”

2. Where does culturehacking sit within wider hacker culture?

“The essence of hacking is that you’re surrounded by alienating infrastructures of various sorts, whether it’s the university management that you have to deal with as a student, or whether it’s my phone, which I can interact with but have no idea how it works,” Brett explains. “Hacking has always been about trying to get behind the interfaces; figure out how your phone works or figure out how management structures actually work. So, it’s an attempt to de-alienate yourself by going behind the boundaries of things, and that’s hacking’s initial exploration impulse – and you can do it with the financial sector. But then what do you try to do with that knowledge? Well, you can try to breach those structures.”

3. Can culture really be hacked?

“The logical thread in my work scrutinises media and looks at the ways you can use media to critique itself,” explains Heba. She first began her subversive work after seeing the media’s response to former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmedinejad’s visit to the US, during George W. Bush’s presidency in 2007. The New York Daily News‘ front page read, ‘The evil has landed’. “It really kind of brought these questions of authority and of surveillance,” she explains.

Right: against the red, blue and purple devil (A Muslim Brotherhood reference made by an Egyptian general on Television in 2013)

Left: Homeland is a joke, and it didn’t make us laugh (photos courtesy of the artists)

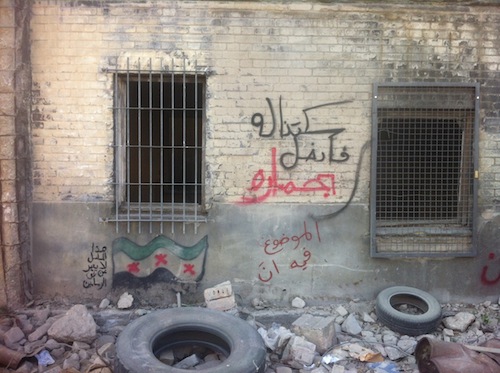

Top: we didn’t resist, so he conquered us riding on a donkey. Bottom: The situation is not to be trusted. Left: This show does not represent the views of the artists (photos courtesy of the artists)

In her native Egypt, after the failure of the Arab Spring, the media has been a key tool of control for General Sisi’s authoritarian dictatorship. But similar patterns of control are also visible in the “free and democratic” West. One example is US series Homeland, which spreads disinformation about the War on Terror and perpetuates negative stereotypes about the Middle East. As previously detailed in Huck, Heba and the ‘Arabian Street Artists’ were invited by the show’s producers to dress their Syrian refugee camp set with realistic graffiti. “This offered the possibility of doing something subversive,” Heba explains. When the slogans they scrawled across the set in Arabic appeared on primetime TV, such as ‘Homeland is racist’, ‘1001 Calamities’, and ‘Homeland is a Watermelon’, it sparked a global debate about the show’s ignorance of its subject matter, orientalist narratives and propagandism.

4. How do you become a culturehacker?

“When I used the term culturehacking in my book The Heretic’s Guide to Global Finance, I was referring to the process by which you break into organisations in order to discover what goes on inside them and to explore them,” Brett explains. “I entered into the financial sector trying to uncover the rule systems and principles at play. I drew on my background in anthropology but just worked in the industry for two years. It was a fascinating process to see how essentially some of the most powerful organisations in the world work and how banal and how ordinary they are, as well.”

“A lot of people outside these types of organisations always imagine them to be these kind of like devious, deviant things,” he continues. “But actually if you’re thinking about GCHQ and the NSA for example, I can guarantee you the NSA is probably one of the most banal places to be every day – it’s probably very boring. There are routinised ways of existing in these organisations, but you only get that experience if you immerse yourself in it.”

5. Subversion can set you free

“I think humour is a really interesting way to subvert the narrative and start a discussion,” Heba explains. She highlights the example of Egypt, where freedom of speech has been severely curtailed following the popular outpouring of everything from street art to music to poetry during the revolution in 2011. Despite the dark cloud that has fallen over the country and the aggressive policing of dissent by the security services, outbreaks of creative criticism still break through. “There’s this idea that a cap has been put on creativity,” she explains. “True, it’s much more difficult to express yourself, for example on social media, as many Facebook administrators are now being being detained. Having said that, there are still people doing things.”

“For example, on the fifth anniversary of the revolution on January 25th, a guy went out to celebrate and mocked the police state by handing out blown-up condoms as balloons,” she continues. “That suddenly became an internet meme and now everybody is inserting images of condoms to comment on the revolution and poke fun at where we are today. So, in a way I think these things are never really shut down. No matter how extreme things might get, I think there are always people who are willing to take risks. Those people then open it up further, for artists and activists and for anyone to insert a moment of subversion.”

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

From his skating past to sculpting present, Arran Gregory revels in the organic

Sensing Earth Space — Having risen to prominence as an affiliate of Wayward Gallery and Slam City Skates, the shredder turned artist creates unique, temporal pieces out of earthly materials. Dorrell Merritt caught up with him to find out more about his creative process.

Written by: Dorrell Merritt

In Bristol, pub singers are keeping an age-old tradition alive

Ballads, backing tracks, beers — Bar closures, karaoke and jukeboxes have eroded a form of live music that was once an evening staple, but on the fringes of the southwest’s biggest city, a committed circuit remains.

Written by: Fred Dodgson

This new photobook celebrates the long history of queer photography

Calling the Shots — Curated by Zorian Clayton, it features the work of several groundbreaking artists including Robert Mapplethorpe, Sunil Gupta, Zanele Muholi and more.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Krept & Konan: “Being tough is indoctrinated into us”

Daddy Issues — In the latest from our interview column exploring fatherhood and masculinity, UK rap’s most successful double act reflect on loss, being vulnerable in their music, and how having a daughter has got Krept doing things he’d never have imagined.

Written by: Robert Kazandjian

Vibrant polaroids of New York’s ’80s party scene

Camera Girl — After stumbling across a newspaper advert in 1980, Sharon Smith became one of the city’s most prolific nightlife photographers. Her new book revisits the array of stars and characters who frequented its most legendary clubs.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Bad Bunny: “People don’t know basic things about our country”

Reggaeton & Resistance — Topping the charts to kick off 2025, the Latin superstar is using his platform and music to spotlight the Puerto Rican cause on the global stage.

Written by: Catherine Jones