Documenting the disappearing bicycles of Beijing

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Xiaomeng Zhao

Rush hour in Beijing is still an amazing sight. Cycle tracks take up multiple lanes of the main avenues and cyclists can do little but be swept along by the densely packed human river of bikes.

China was once known as the ‘Kingdom of Bicycles’, but long gone are the days when the humble bicycle was the only game in town. As China has boomed in recent decades, the car has become a symbol of status, and the once ubiquitous bicycle has been abandoned by most. Today, cyclists are increasingly losing space to those on four wheels.

Photographer Xiaomeng Zhao has fond memories of cycling during his childhood, but sees the disappearance of the country’s bicycles as a reflection of the huge changes to Chinese society.

Xiaomeng scoured Beijing to discover the fate of the city’s lost bicycles. He found many in states of dysfunction and disrepair, yet still too treasured to be thrown away by their owners.

His Bicycles in Beijing, Now series reveals that bikes remain highly valuable to the city’s marginalised groups, such as poorer and older people, or migrant workers from rural areas – the people who can’t afford cars and who reveal that China’s growth and prosperity has still not been felt by all.

Why did you feel the bicycle was a powerful symbol to express the pace of social change in China?

Soon after the declaration of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, bicycles became the most important means of transportation for everyone. I was born in the late ‘80s and the bicycle was not only a necessity for travelling but also part of our lifestyle. Until I went to high school, riding to school with my friends was the most memorable and joyful time of my childhood.

After graduating I went overseas to continue studying in Canada. I recently returned to China, and see these bicycles again while strolling in the city. They immediately reminded me so much of my childhood. But today they’re are not in good shape, they’re broken and abandoned. I thought the conditions of these bicycles and their status in society reflected the changes China been through in recent years.

Could you share story behind making one of the images?

The process of making these photos was full of surprises. People become quite creative with their bikes, and you can’t imagine or underestimate their inventiveness. One of my favourite images shows a classic Beijing tricycle, where there is a seat at the back; Perhaps the back of the seat was exposed and it wasn’t very pleasant looking, so the owner mounted a cropped wedding portrait to replace the broken back.

It made me laugh for quite long time as I stared at it from the street corner. I thought, “Well, I’m not sure about this marriage but at least this bike is still working.” I think if Marcel Duchamp walked into Beijing’s hutong today he might go crazy, because every bicycle is a piece of ready-made art.

Living in Copenhagen, I’m sure you’re perfectly aware of how the bicycle has been re-embraced in the West, partly in response to climate change and overcrowding in cities. Do you see a resurgence of the bicycle in China?

I certainly hope to see a new golden age for bicycles in China, but that might take a very long time, as the issue right now is not solely transportation. As a result of China’s rapid economic shift, people’s values have changed and cars are the new vehicle of choice. The newer generation of Chinese equate the level of success to the kind of car they own. To them, bicycles are for the less fortunate.

Even when it comes to civil planning, the government has developed urban areas focusing on automobile transportation. Lots of public space, whether it’s bicycle lanes or pedestrian lanes, have now turned into vehicle lanes or parking lots. To change all of this and have people return to bikes again will take a long time.

Who still rides bikes in China today? You mentioned in your artists statement that ‘cycling has been reduced to a sign of the socially vulnerable groups in China.’ Who are these people and why are bicycles still important to them?

In Beijing, I mainly see elders, or people living in the poorer areas, who are from outside of Beijing looking for work and aren’t making enough to afford a car. These people are being treated the same way as the bicycles — constantly distorted and marginalised by the society.

‘Why are bicycles still important to them’ is a great question. From the images you can see that many bikes are quite damaged, but people would find clever ways to patch them up. Though some pieces are already considered junk, instead of giving them up, the owners would still spend a lot of time and thought on repairing them.

I think to these people, this act of fixing may give them simple pleasures, and also upholds their dignity in a way. They have been left behind by the abrupt changes in the world, but they insist on holding on to the little they have, and trying to preserve the bond they have with the objects. It’s another reason to keep on living, or to remind them of a reason to live.

Western audiences struggle to understand how much has the immense pace of development in China has really changed life for ordinary people. Could you give a personal example?

To me, the biggest change or challenge people face is the pressure of living a sound life. When I returned to Beijing these days, I found it hard to meet up with my old friends for a beer, they are so caught up with their work. Even when we meet, our topics would revolve around work stress, or how much it costs to buy a house, or what’s the price for that new car. It gives me the impression that making money and spending money has become the only life goal.

When I had this conversation with my parents, they agree that our generation has become too materialistic compared to the late ‘70s and ‘80s, where life was more about simple pleasures, despite the low GDP. Right now, every product we buy is constantly perfected but no one is happy.

In China, I often hear the mainstream media say that what we achieved economically in the past 30 years is comparable to what the West achieved in the past 300 years. It’s undeniable that China has accomplished so much, and the quality of living has improved dramatically. But at the same time does this mean we’ve also amassed 300 years worth of unresolved problems in such a short period of time? How long would it take for us to resolve these problems? Are we going to lose our precious history and traditions in the process? I think these will be the questions we need to face in China.

Find out more about Xiaomeng Zhao’s work.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

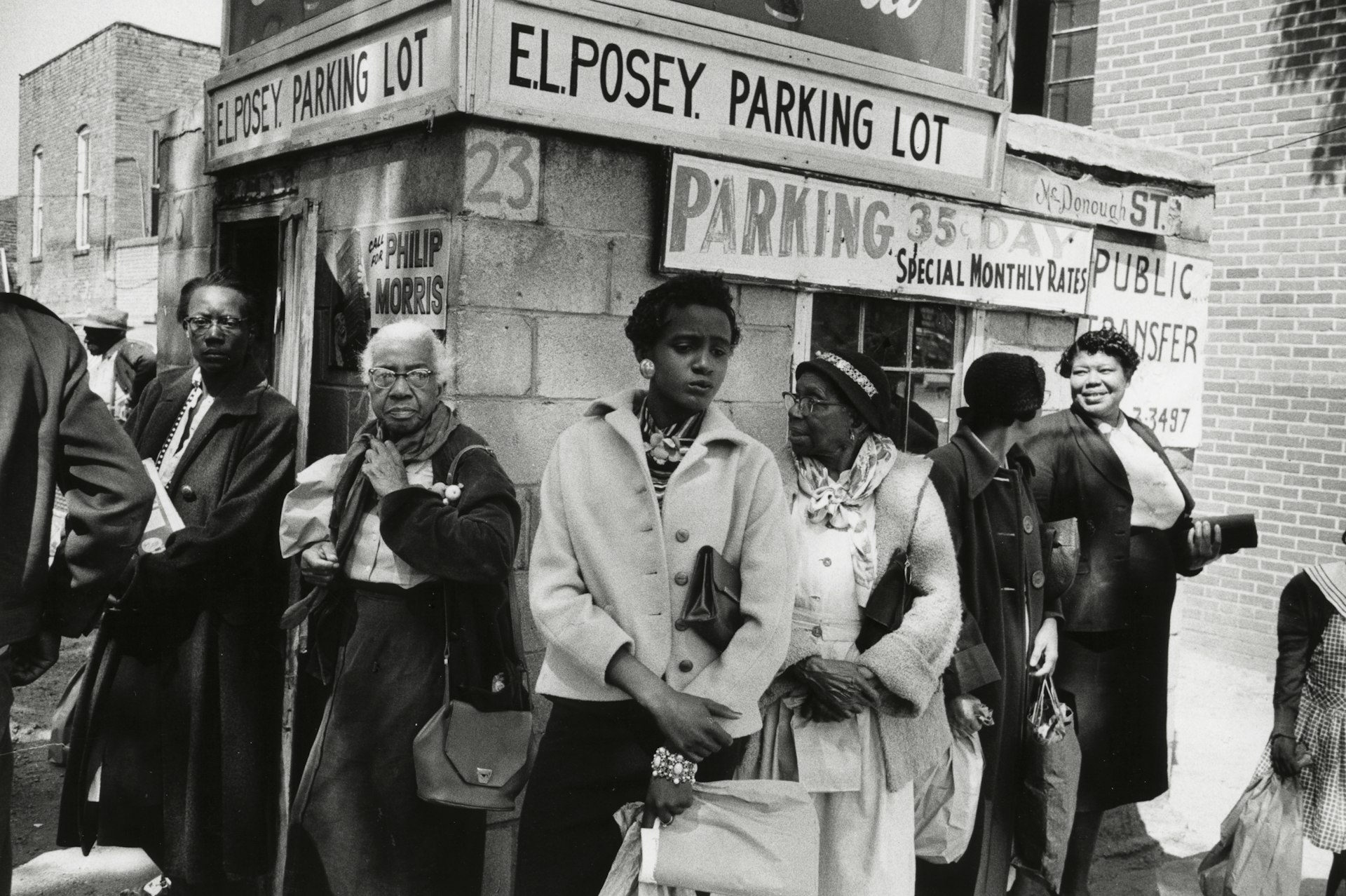

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk

“Welcome to the Useless Class”: Ewan Morrison in conversation with Irvine Welsh

For Emma — Ahead of the Scottish author’s new novel, he sat down with Irvine Welsh for an in-depth discussion of its dystopic themes, and the upcoming AI “tsunami”.

Written by: Irvine Welsh