These portraits capture America’s changing face

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Dawoud Bey

At the age of 16, New York native Dawoud Bey traveled from his home in Queens to see Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968, the controversial exhibition that opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969.

As he gazed upon the portraits that James Van Der Zee made during the Harlem Renaissance, Bey recognised the profound power of the photograph to become both a repository for communal memory and a portal into another era – one that informs the way we live and think today.

This innate understanding of the portrait at a young, formative age, provided the foundation upon which he has built a tremendous, transformative body of work. Over the past half a century, Bey’s photographs have become both art and artefact, evidence and testimony, document of the moment and letter to the future.

Three Women at a Parade, Harlem, NY, 1978

His new book – titled Dawoud Bey: Seeing Deeply – is an illustration of an incomparable photographer: one that places empathy, respect, and determination at the centre of their work. Featuring selections from his most important (including Harlem, U.S.A., Class Pictures, The Birmingham Project, and Harlem Redux), it’s an all-encompassing journey through Bey’s career.

“Under the influence of Roy DeCarava, Lou Draper, and other black photographers from the Kamoinge Workshop, I began photographing everyday African Americans in Harlem,” Bey explains. “Early on, the streets were a public theatre, a space where lives were being lived. I wanted to enter that space and describe some of those black lives through my own photographs.”

“I had also spent time looking at the works of photographers like Irving Penn and his Small Trades photographs along with the Heber Springs portraits of Mike Disfarmer. Both gave me a sense that ordinary people directly engaging the camera could lead to something quite powerful. Those studio photographs became even more meaningful to me in later work when I entered the studio myself.”

Lauren, Gateway High School, San Francisco, CA, 2006

Seeing Deeply reveals Bey’s transition from street to studio in order to free his subjects from social signification of their environment. By training his eye of the qualities of gesture and expression, he fine-tuned his ability to capture the moments when feelings and thoughts cross the face.

“For all of the ways that they engage us, photographs are inherently mute. They can only describe the world inside of the frame. There is always more that we don’t know, and that contextualising information lies outside the frame,” he adds.

In the book’s final chapter, Bey returns uptown for Harlem Redux, a portrait of the now. It is the story of a place as an extension of self and the way in which the very fabric of culture, tradition, and community lies in the very land upon with it rests.

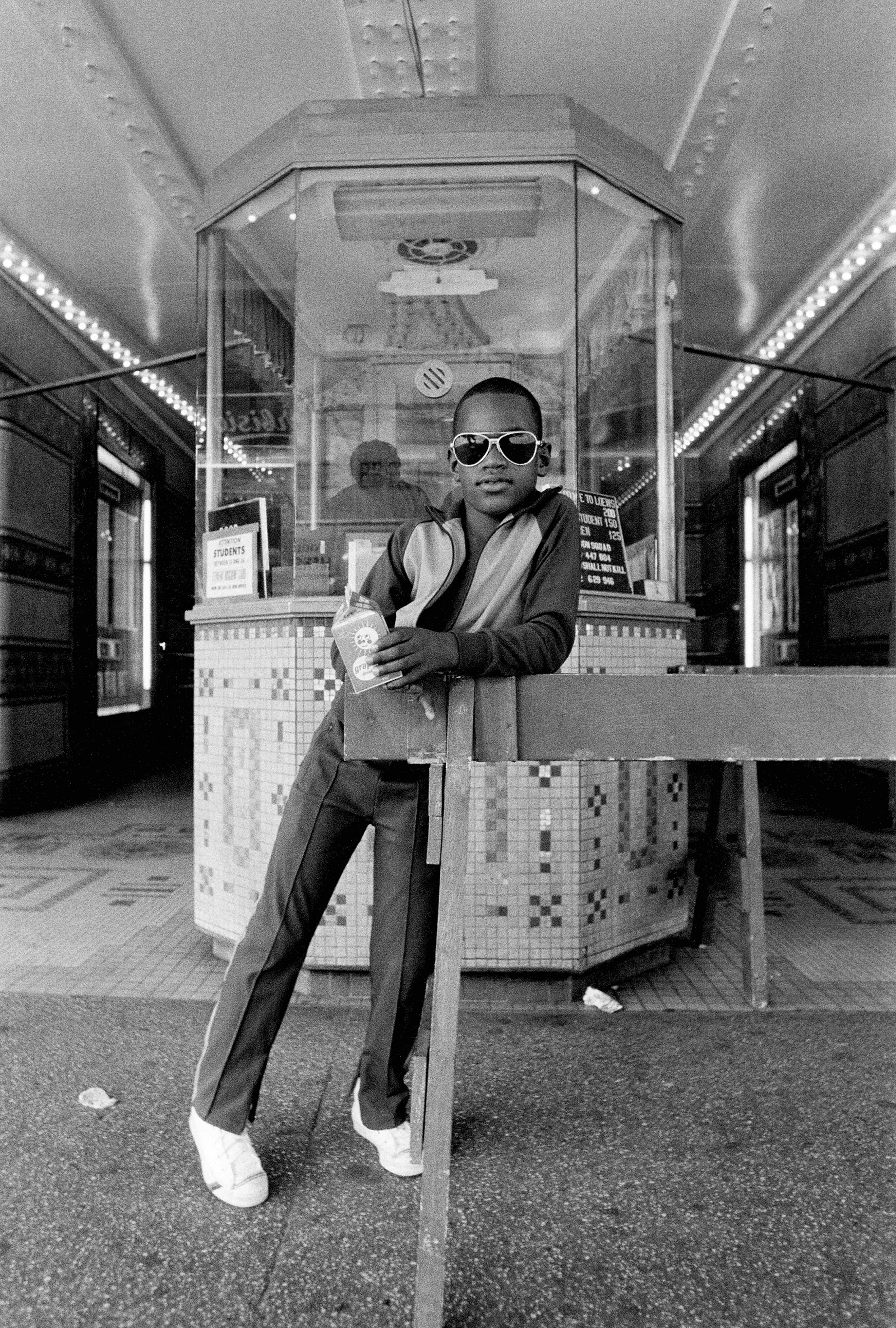

A Boy in Front of the Loew’s 125th Street Movie Theatre, Harlem, NY, 1976

The Harlem of the 1970s that Bey knew has all but disappeared as a new kind of systemic destruction is afoot. “There is and increasing disruption of place memory as significant pieces of the community’s history are torn down and replaced by big box chain stores and luxury apartment towers,” he notes.

“It took me a year of persistently photographing before I figured out the language that I needed to make that work, and to wrap a sense of visual poetics around this rather disruptive thing that is taking place in Harlem…and in a number of communities across the country.”

A Woman and Her Daughter at Salinas Street Bus Stop, Syracuse, NY, 1985

Amishi, Chicago, IL, 1993

Two Girls at Lady D’s, Harlem, NY, ca. 1976

Elliott Brown and Sophia Woolery, Tacoma, WA, 2013

Charita, 2002

A Girl with School Medals, Brooklyn, NY, 1978

A Girl with School Medals, Brooklyn, NY, 1978

Martina and Rhonda, Chicago, IL, 1993

Dawoud Bey: Seeing Deeply is available now from University of Texas Press.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Clubbing is good for your health, according to neuroscientists

We Become One — A new documentary explores the positive effects that dance music and shared musical experiences can have on the human brain.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

In England’s rural north, skateboarding is femme

Zine scene — A new project from visual artist Juliet Klottrup, ‘Skate Like a Lass’, spotlights the FLINTA+ collectives who are redefining what it means to be a skater.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Donald Trump says that “everything is computer” – does he have a point?

Huck’s March dispatch — As AI creeps increasingly into our daily lives and our attention spans are lost to social media content, newsletter columnist Emma Garland unpicks the US President’s eyebrow-raising turn of phrase at a White House car show.

Written by: Emma Garland

How the ’70s radicalised the landscape of photography

The ’70s Lens — Half a century ago, visionary photographers including Nan Goldin, Joel Meyerowitz and Larry Sultan pushed the envelope of what was possible in image-making, blurring the boundaries between high and low art. A new exhibition revisits the era.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The inner-city riding club serving Newcastle’s youth

Stepney Western — Harry Lawson’s new experimental documentary sets up a Western film in the English North East, by focusing on a stables that also functions as a charity for disadvantaged young people.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The British intimacy of ‘the afters’

Not Going Home — In 1998, photographer Mischa Haller travelled to nightclubs just as their doors were shutting and dancers streamed out onto the streets, capturing the country’s partying youth in the early morning haze.

Written by: Ella Glossop