Why bringing instant photography back is not Impossible

- Text by Hanna Duggal

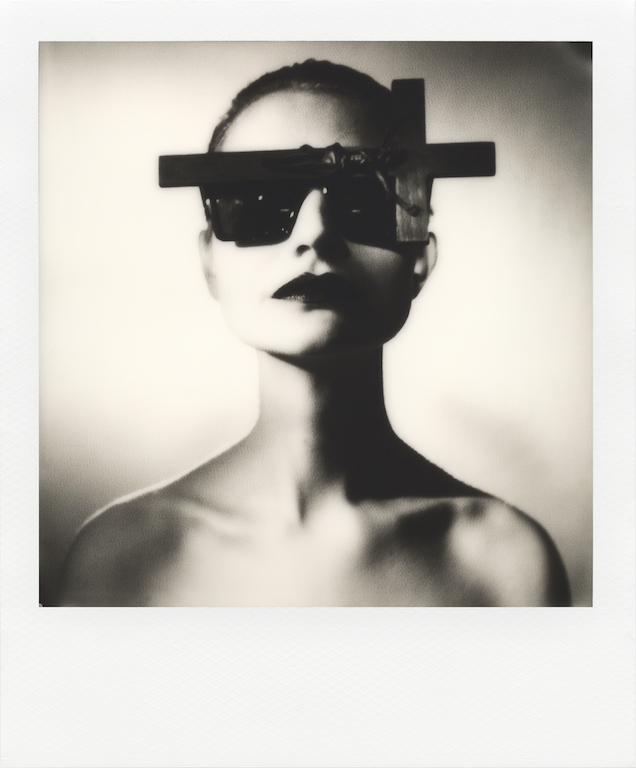

- Photography by Oliver Blohm

In a Shoreditch warehouse the launch of the new Impossible I-1 camera is taking place. The interior brick walls of the compound host images from various photographers – all shot on instant film. The passé quality of polaroid-style shots is a time-honoured token of a period where there was no click and delete after taking a photograph. It’s a reminder of the material photograph rather than the digital file.

Impossible I-1 features an app where all the controls possible on a professional camera are applied. Everything from flash to aperture can be controlled and with manual mode subtle adjustments are possible, so in one sense it’s not just a point-and-shoot camera. It’s old school but the introduction of the app has made it a practical medium for professional photographers.

German photographer Oliver Blohm has been shooting analogue for a long time; he has worked on various projects from microwaving photographs to shooting editorial. For Blohm it’s not about snapshotting an image, it’s about creating one. His collaboration with Impossible began by chance back in Berlin – after he struck up a conversation with a like-minded photographer who was doing workshops with Impossible.

What’s the most gratifying thing about instant film?

It’s the possibility to create something unique. With every picture you take you will get something different; one big opportunity or emotional factor is that you have a real picture to hand, and not an artificial, digital file that you have somewhere on your hard drive or memory card. It’s something you can see after a few seconds, or a few minutes, and you can base your next step on the real image, not on the digital file, where you know you will work a lot with Photoshop after it.

Some of your work is displayed here – it’s very artistic. What do you hope people will see in your images and how will that translate to them using the camera?

I think people will need to study a little bit further. The selection that was made by the makers is a very wide one. When you are here you can see very different images and I think my aim in all of my pictures is that you can see that it’s not a snapshot – it is something that is created by something. It’s something that is, on the one hand very artistic – it can be very intimidating, very spontaneous but on the other hand very focused, concentrated and prepared.

How relevant do you think instant film is in this digital age?

How relevant do you think instant film is in this digital age?

I think it’s an important thing. I have the feeling that people get bored by this super-fast developing, technical thing that is going on in our society. When you see here around the corner a market with food and everything is self-made and prepared – people want to get something real again. The hashtag is #makerealphotos – that’s the point of instant film and Impossible in our society, because it’s real.

What is special about photographs made with the I-1?

For two years I worked with 8×10 photography. At first the I-1 felt like a toy but getting closer and closer with this camera, the app and manual control mode I realised that it’s technically not that far away from an 8×10 camera – I have all my controls, I can set the focus, flash, shutter speed and aperture. It’s smaller. For me it’s the same kind of manual and handcrafted work and building a picture instead of snapshotting.

Polaroid and instant film have a very distinct place in history. Why is it important to keep it alive?

There are a lot of things in history – I think we need to keep history alive, on one hand to learn from history and on the other hand there are a lot of really beautiful, impressive, important things made in history – beginning from furniture, from fashion design, from design in general to a handmade picture. Photography started with handmade photography and a real picture to hand; it’s good that it’s still alive because even if it’s not the beginning of photography it’s a part of the beginning.

It’s kind of like how vinyl’s made a comeback…

Yes. I have a vinyl player and a lot of vinyls and I would say I hear the difference from a CD or computer to vinyl. When I come home it’s like I don’t need to turn on my computer, I don’t need my iPad, I don’t need my smartphone. I just go home, put my stuff on the ground, go to my vinyl player, open it and put the needle on the player. Then it’s on. There is just one button that turns on the receiver and the only other step is to slightly put the needle on the vinyl and then there’s music. There’s no waiting time, no loading time, no electricity, no light. It’s just what it is. It’s music. It’s not an equaliser. It’s on the point. It’s like an instant photo – you make it, you wait for it, you get it and that’s what you have.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

In the ’60s and ’70s, Greenwich Village was the musical heart of New York

Talkin’ Greenwich Village — Author David Browne’s new book takes readers into the neighbourhood’s creative heyday, where a generation of artists and poets including Bob Dylan, Billie Holliday and Dave Van Ronk cut their teeth.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk