The highs and lows of a whirlwind romance, in photos

- Text by Ada Bligaard Søby, as told to Cian Traynor

- Photography by Courtesy of Ada Bligaard Søby, Louis My

My ex-boyfriend Louis was 10 years older than me and led a wild, improvised life. He grew up as an orphan, squatted as a punk in London and had a son from a previous relationship. I was 21 when we met and was immediately drawn to this treasure trove of pictures he’d accumulated. Being an inexperienced person just starting out as a photographer myself, I was probably in awe of that.

A few years ago, I kept seeing updates from Louis popping up on Facebook. He was living in Asia, constantly posting photos of what he was doing while taking the piss out of himself. It cracked me up so much that it gave me an idea. I thought back to the pictures of us as a couple in New York during the ’90s and started imagining how he’d caption them.

I wondered what it would be like to see our worlds in parallel: a visual timeline that mapped out the directions of our lives, both before and after the relationship, as a photobook. Louis and I had remained friends, catching up on the phone maybe once a year, so when I broached the idea, he said: “Okay, let’s do it!”

Somehow we managed to get all these photos – stored with another ex-girlfriend in Montreal – shipped to France, where we met up at his sister’s house and went through everything. It was the first time we’d seen each other in 17 years and I quickly realised how insane this idea was.

It’s incredibly difficult to trawl through your own history and try to make sense of every turn you’ve taken. Even though you might cherish those moments, there are plenty of regrets and bad memories there too.

Ada: “The day after we met, a photographer snapped us on the boardwalk at Coney Island. A year later when we were looking around a magazine shop in Paris, we found ourselves in a cheesy Turkish ad for God knows what.”

Louis and I come from different backgrounds. I grew up in a 17th century castle that houses Denmark’s National Portrait Gallery. My mum is an art historian and when she got a job as a curator there, she and my dad – a lawyer – moved in. I was born a year later, in 1975.

It was a beautiful place to live, and I’m super Danish in lots of ways, but when you grow up in a country where the standard of living is so well-balanced, things can seem boring or even numbing.

At 16, I moved to rural Saskatchewan in Canada as an exchange student. Being a foreigner in a little town allows you to discover lots of secrets. It was an extremely religious place and yet, beneath the surface, there was alcoholism, affairs, teenage pregnancies, boredom and despair.

Then at 20, I moved to New York and – as weird and gritty as it was – that same dynamic still lingered: there are the stories we tell ourselves and then there’s what’s really going on. That’s a big part of what motivates my work, and the dichotomy of this book. Louis was someone who loved to bring out the truth in things and confront these contrasts.

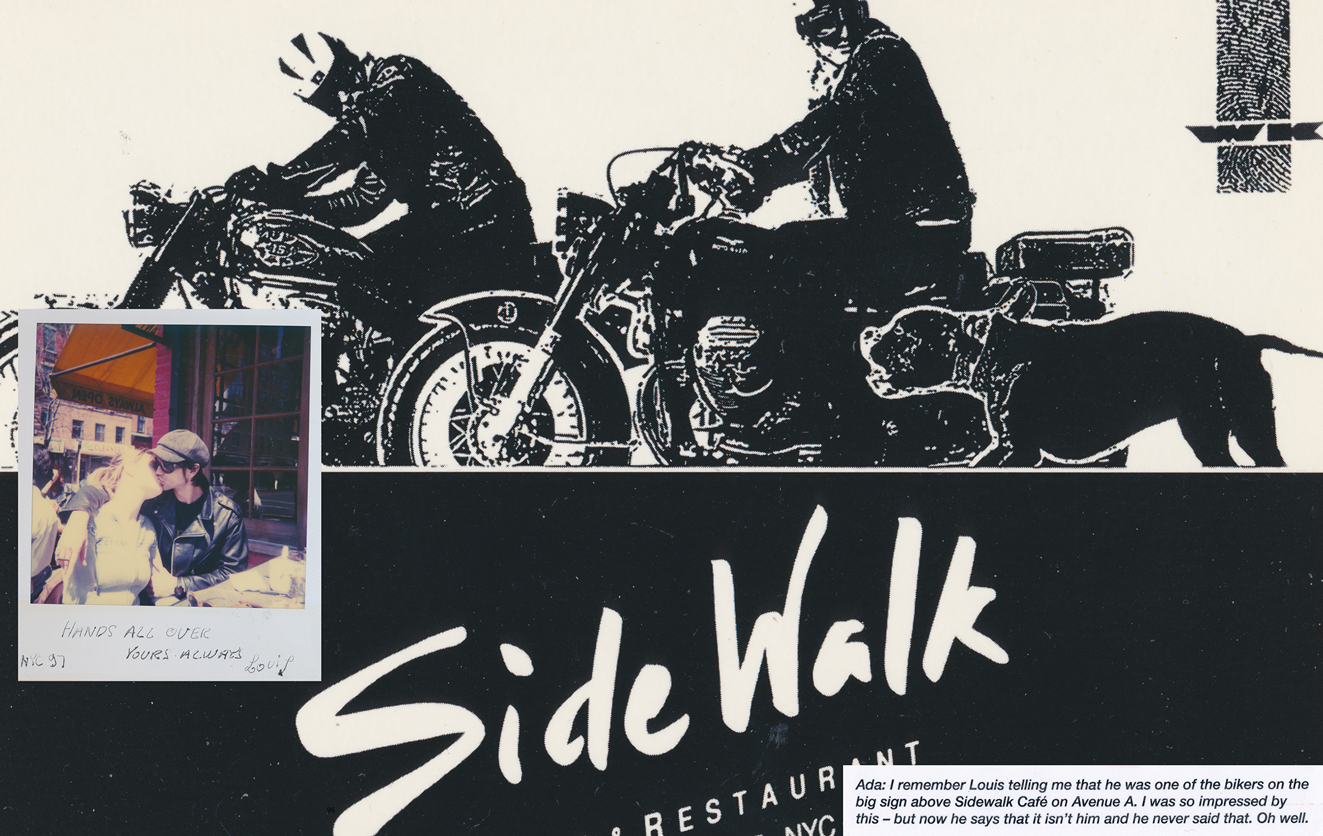

When we met, he was living in a storefront in the East Village with two motorbikes parked inside his own apartment, a drum kit and a loft bed squeezed in the back. Everything smelled like gasoline. You can’t really get further away from a castle than that. Often you take pictures because you don’t understand something, or because you’re trying to contain it.

So I started documenting our life together: just walking around, taking road trips and soaking up so much culture. It was magical. I don’t know what track I was on but Louis sent me off in a different direction. He taught me not to be a scared little girl from a castle, to go after my dreams like a badass, to stay away from drugs and never let anyone bring me down.

There are events in life that change your understanding of the world, where you see yourself in a different light and things will never be the same again. I think that’s what Louis was for me. We were together for two years but it felt like 15.

In the end, I think the New York experience was too much to take in at that age. Louis was also in a horrible motorcycle accident and had to go back to France to be treated. Our American adventure ended simultaneously and that pained us both.

I think that’s why this project proved to be so fragile. As a documentarian, I’m used to digging around in other people’s emotions. With this, we’re tinkering with our own complex feelings, perceptions and ideas of legacy – pretty much the definition of opening old wounds. There were arguments, exhaustion, hurt. But I believe that art is supposed to be uncomfortable and push boundaries. Otherwise it is useless.

Even though I was probably a pain in the ass about this project, our friendship has survived. I’m a different woman than when we first met – now with a billion experiences and opinions – and I felt like Louis gave me his blessing to do it the way I wanted, which is a credit to him.

To do a book about life and love with your ex is an almost impossible task, but I’ve never had such positive feedback for anything I’ve worked on. I think everyone can relate to the fact that when you step back and look at it, life can be complicated… but also absurd and magic.

The Best is Yet to Come is published by Kehrer Verlag.

This article appears in Huck 67 – The Documentary Photography Special VI. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe now to never miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Clubbing is good for your health, according to neuroscientists

We Become One — A new documentary explores the positive effects that dance music and shared musical experiences can have on the human brain.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

In England’s rural north, skateboarding is femme

Zine scene — A new project from visual artist Juliet Klottrup, ‘Skate Like a Lass’, spotlights the FLINTA+ collectives who are redefining what it means to be a skater.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Donald Trump says that “everything is computer” – does he have a point?

Huck’s March dispatch — As AI creeps increasingly into our daily lives and our attention spans are lost to social media content, newsletter columnist Emma Garland unpicks the US President’s eyebrow-raising turn of phrase at a White House car show.

Written by: Emma Garland

How the ’70s radicalised the landscape of photography

The ’70s Lens — Half a century ago, visionary photographers including Nan Goldin, Joel Meyerowitz and Larry Sultan pushed the envelope of what was possible in image-making, blurring the boundaries between high and low art. A new exhibition revisits the era.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The inner-city riding club serving Newcastle’s youth

Stepney Western — Harry Lawson’s new experimental documentary sets up a Western film in the English North East, by focusing on a stables that also functions as a charity for disadvantaged young people.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The British intimacy of ‘the afters’

Not Going Home — In 1998, photographer Mischa Haller travelled to nightclubs just as their doors were shutting and dancers streamed out onto the streets, capturing the country’s partying youth in the early morning haze.

Written by: Ella Glossop