Snapshots of London’s streets during Thatcher’s Britain

- Text by Charlotte Rawlings

- Photography by Sunil Gupta

Indian-born documentary photographer Sunil Gupta is speaking to me via video call from his vibrant studio in Camberwell. He turns his screen to reveal a jungle of boxes and folders; shelf after shelf of negative film. These photographs, which he took in the streets of London during the early 1980s, have been stored away and forgotten for almost 30 years, he tells me. They’ve only resurfaced recently, with the release of his latest photo book, London 82.

Gupta spent 1976 in New York photographing the prominent gay scene of Christopher Street, the site of the 1969 Stonewall riots, which had since become the beating heart of a thriving gay community. When he moved to the UK and settled in Parsons Green, Gupta expected to capture a similar energy around Earl’s Court, King’s Road, and the West End, but to no avail.

The photographer struggled to establish anywhere with a strong gay presence. “The [UK] government itself had very homophobic laws,” Gupta says. “Although we legalised gay sex here at the end of the ‘60s, they still criminalised cruising.”

This meant there were fewer safe spaces for people to openly express their sexuality. With this in mind, Gupta abandoned his idea to exclusively photograph London’s gay scene. He noted that photographing people who he thought might be gay would risk outing them or harming them in some way. So, instead, he simply chose to photograph anyone that caught his eye.

Gupta made a point of capturing an eclectic mix of people: a pensioner crossing the road, a cigarette hanging between her lips; a punk striding past the grounds of a barracks in Chelsea; two women juggling take away food while sporting a pair of chic winter coats.

Gupta notes that the early days of Thatcherism were an especially hostile time for anyone who wasn’t white, straight, and wealthy. New York had felt different. Gupta had arrived there after Stonewall’s transformative impact on the gay liberation movement and before the AIDS crisis, and he’d found the city to be largely “positive and affirming” when it came to one’s sexuality.

“Hundreds of people migrated to New York and were participating in this very public display,” he explains. “It was the first time I’d seen a public street that had almost been taken over by a subculture. You didn’t have to go to some nightclub at two in the morning, there were people out in the middle of the day.”

“It was symptomatic of the way in which New York and San Francisco embraced gay subculture and allowed people to be very out and open,” he recounts. “But when I came to London, I didn’t realise it was the opposite.”

Gupta remarks that this was a time when plain-clothed police would attempt to attract the attention of gay men and arrest whoever approached them; a time where you couldn’t hold your partner’s hand in a pub, for fear of being kicked out, or worse. “I found people [in the UK] were fearful and less willing to be publicly out.”

Despite these limitations, Gupta’s photographs still embody the fascinating vastness of London’s population. “There were two extremes,” he says, “there were OAPs [old age pensioners] at my end in Fulham Broadway, who were just getting by; then across into Chelsea and the West End there were people who were obviously very wealthy.”

He explained that before Thatcher, London was rundown. This made it affordable and why those with less money could live so close to the city centre. “Thatcher was going to change that and make it all shiny and new, and expensive.”

Gupta adds: “I was quite impressed, as a newcomer to the city, how London managed to create a mixed housing situation where people were living pretty near each other with very different economic means. That’s not the case in places like New York.”

London’s streets were bustling with different social classes, ethnicities, ages, religions, and maybe less obviously, sexualities. London 82 offers an honest portrait of what it was like to walk those streets at the time. “It’s the end of the Winter of Discontent and just the very beginnings of Thatchersim,” Gupta says of 1982. “I hope [people] can relate to them and that they capture the mood of the time.”

London 82 is available to purchase on Stanley/Barker.

Follow Charlotte Rawlings on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

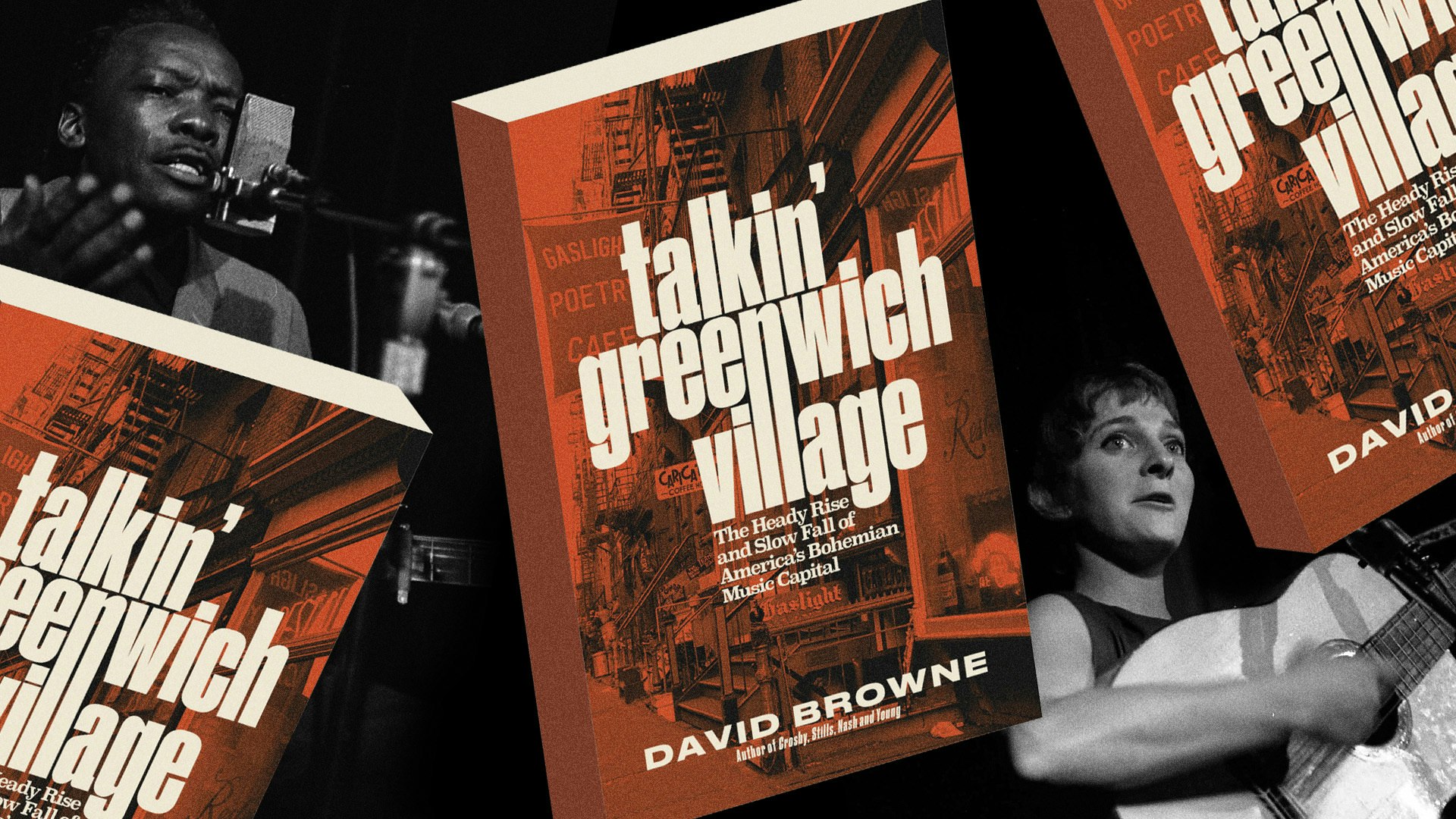

In the ’60s and ’70s, Greenwich Village was the musical heart of New York

Talkin’ Greenwich Village — Author David Browne’s new book takes readers into the neighbourhood’s creative heyday, where a generation of artists and poets including Bob Dylan, Billie Holliday and Dave Van Ronk cut their teeth.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

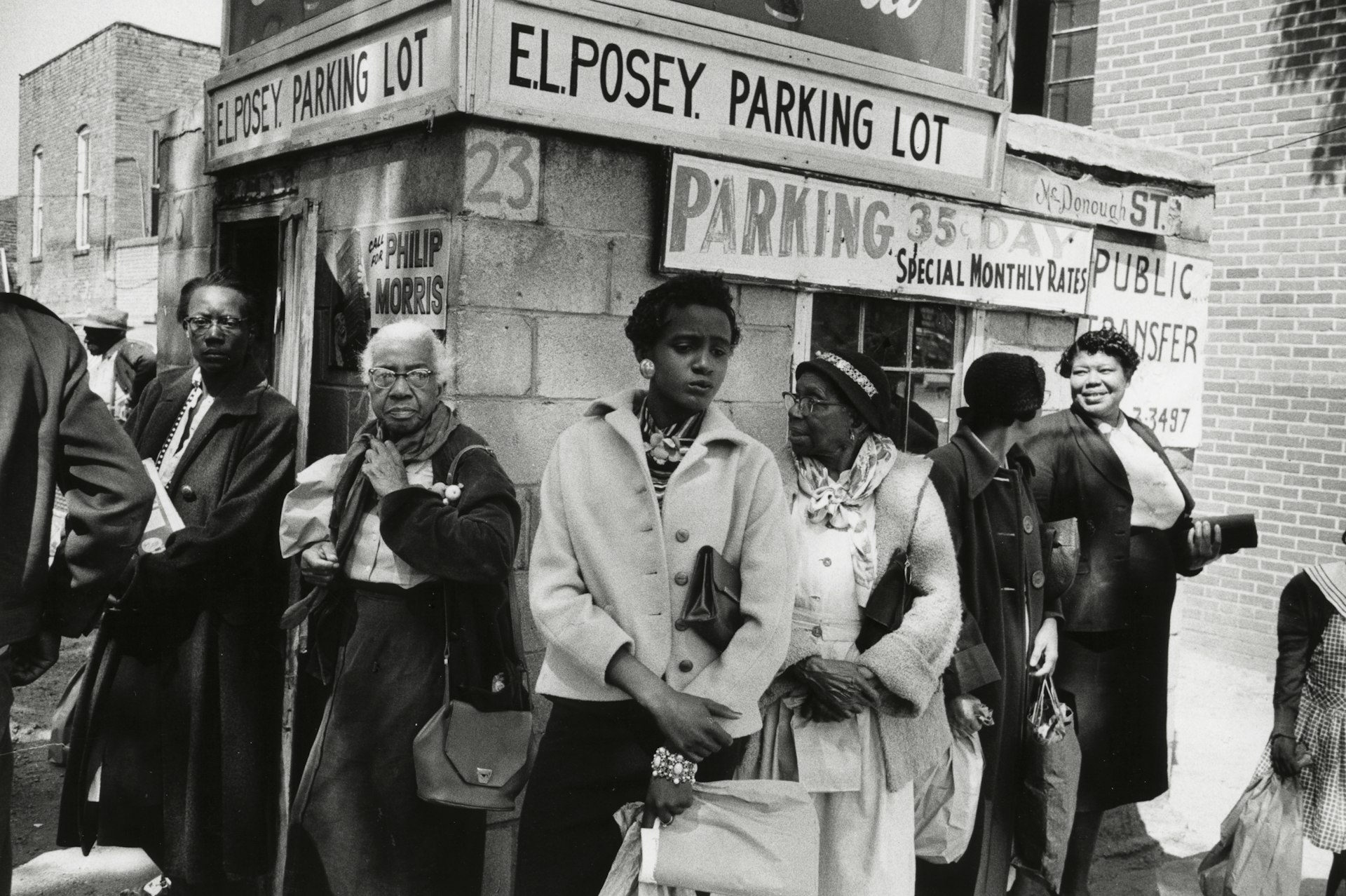

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk