Life on New York’s Lower East Side was notoriously rough before the bougie brunch spots moved in. Home to junkies, squatters, anarchists, artists, musicians and drag queens, tensions reached a peak in 1988 when authorities moved in supposedly to evict a group of homeless people from Tompkins Square Park. It erupted into a full-scale police riot which eventually led to sacking of numerous officers and the reorganisation of the NYPD.

The Satan’s Sinners Nomads street gang emerged out of this pitched battle in Tompkins and the need to protect themselves. But when its leader Cochise was sent to prison for attempted murder of two of its members, the last of the traditional gangs disappeared from the streets of the Lower East Side.

Artist, photographer and local historian Clayton Patterson had been documenting the gang, recognised Cochise’s creative potential and encouraged him to pursue art. Now released from prison, Cochise is an artist and anti-gang counsellor.

In this short from Concrete Cameras by filmmaker Simon J. Heath and Patterson, Cochise talks about his former life as part of a video series on NYC’s underground cultural figures.

We spoke to Cochise to find out more.

How did the Satan’s Sinners Nomads come into being? How and why did you become involved?

The Satan’s Sinners Nomads came into being back in 1988 right after my second prison stint for assault. We evolved in Tompkins Square Park right after the infamous police riot, I formed the club to establish a brotherhood and to defend ourselves/myself from other clubs that were relevant at the time on the Lower East Side. But mainly because I was enamoured with the gang lifestyle and wanted to be a leader.

Do you ever regret anything you did during your gang years? If so, how do you reconcile those actions with yourself?

I do regret the violence and malice I committed toward others but especially the pains and hardship I put my family through. I was the cause for a lot of suffering. Today, I try to be more compassionate towards others and treat others the way I would like to be treated.

What finally led you to leave that life behind? What is your life like today?

I finally left the gang life behind when I came to the realisation that I had become a monster and tried to murder two members of my gang simply because they wanted out of the lifestyle. I desperately sought change when I was finally apprehended. I spent 18 years in prison paying for my crimes. While in prison I participated in all sorts of programmes and finally attained my G.E.D and earned certificates from the University of the State of New York Education Department in Peer Counselling. I also took the opportunity to reach out to other incarcerated gang members and shared my story with them. When I was released from prison I continued in my quest to help others and make myself available.

What was your relation to art before Clayton encouraged you to make work as an artist? What effect has making art had on your life? What are the biggest lessons you’ve learned from making art?

Before meeting Clayton Patterson I didn’t pay much attention to art except to decorate my gang’s club house with skulls and caricatures of death and give it a menacing look. It was Clayton who saw the potential and talent in me and encouraged me to pursue art. Since then I’ve used art to paint a message of hope and life in and out of prison. I especially use it to fight against gangs, drugs and violence. I call it “Art Against Gang Violence.”

How do you feel about being the last LES street gang? Which aspects of the culture are you glad have been left in the past?

The Satan’s Sinners Nomads was the last street gang in the Lower East Side to wear gang colours and I’m glad that it is gone and no longer able to instil fear in peoples hearts. I’m certainly glad it is in my past and no longer able to rise and do any harm. I do miss the people I once knew who lived a similar lifestyle and were absorbed in the gang life but most are dead or in jail. They died violently. They too had the potential to do good but no one will ever know. I am grateful for the second chance.

Latest on Huck

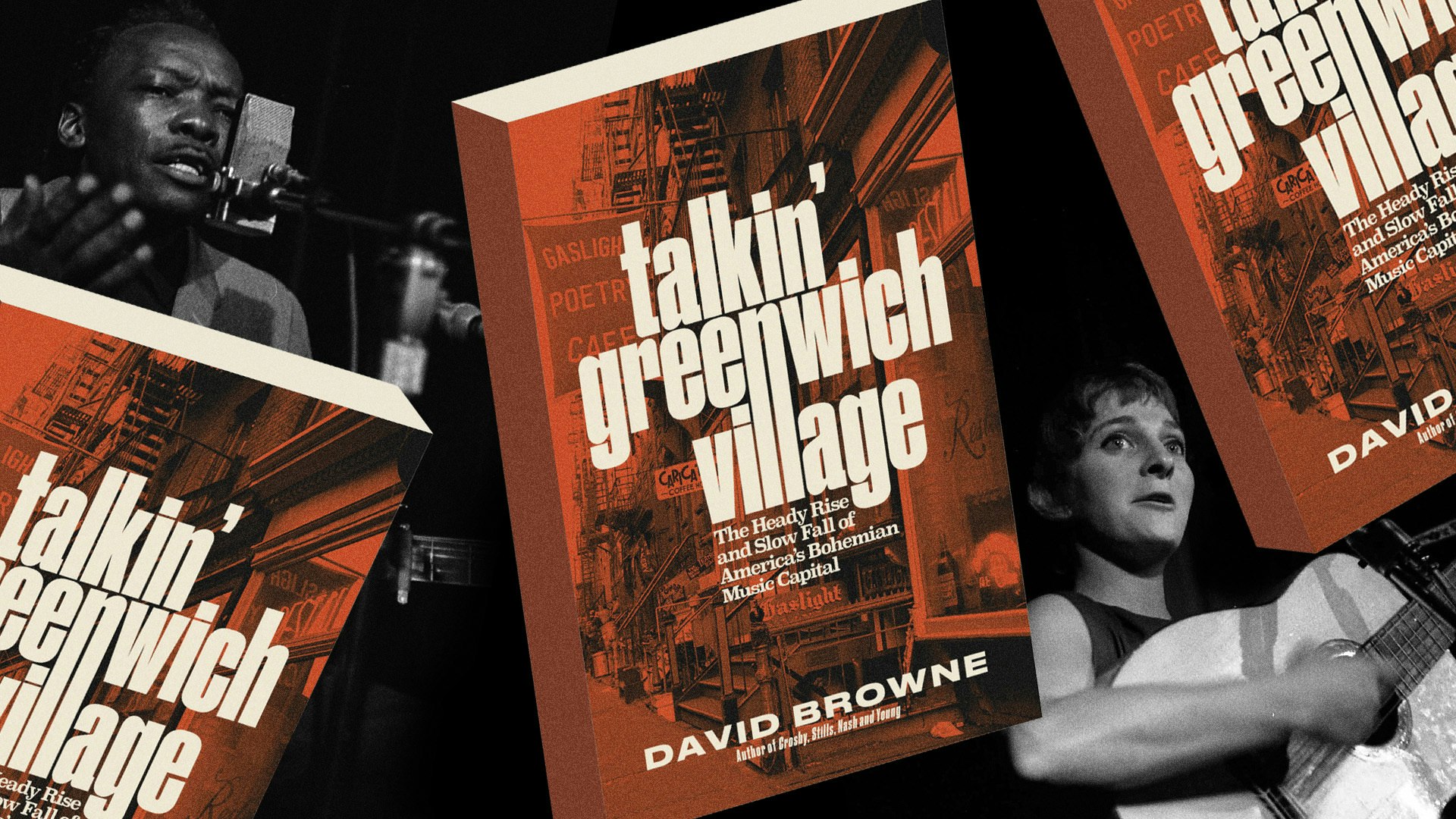

In the ’60s and ’70s, Greenwich Village was the musical heart of New York

Talkin’ Greenwich Village — Author David Browne’s new book takes readers into the neighbourhood’s creative heyday, where a generation of artists and poets including Bob Dylan, Billie Holliday and Dave Van Ronk cut their teeth.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

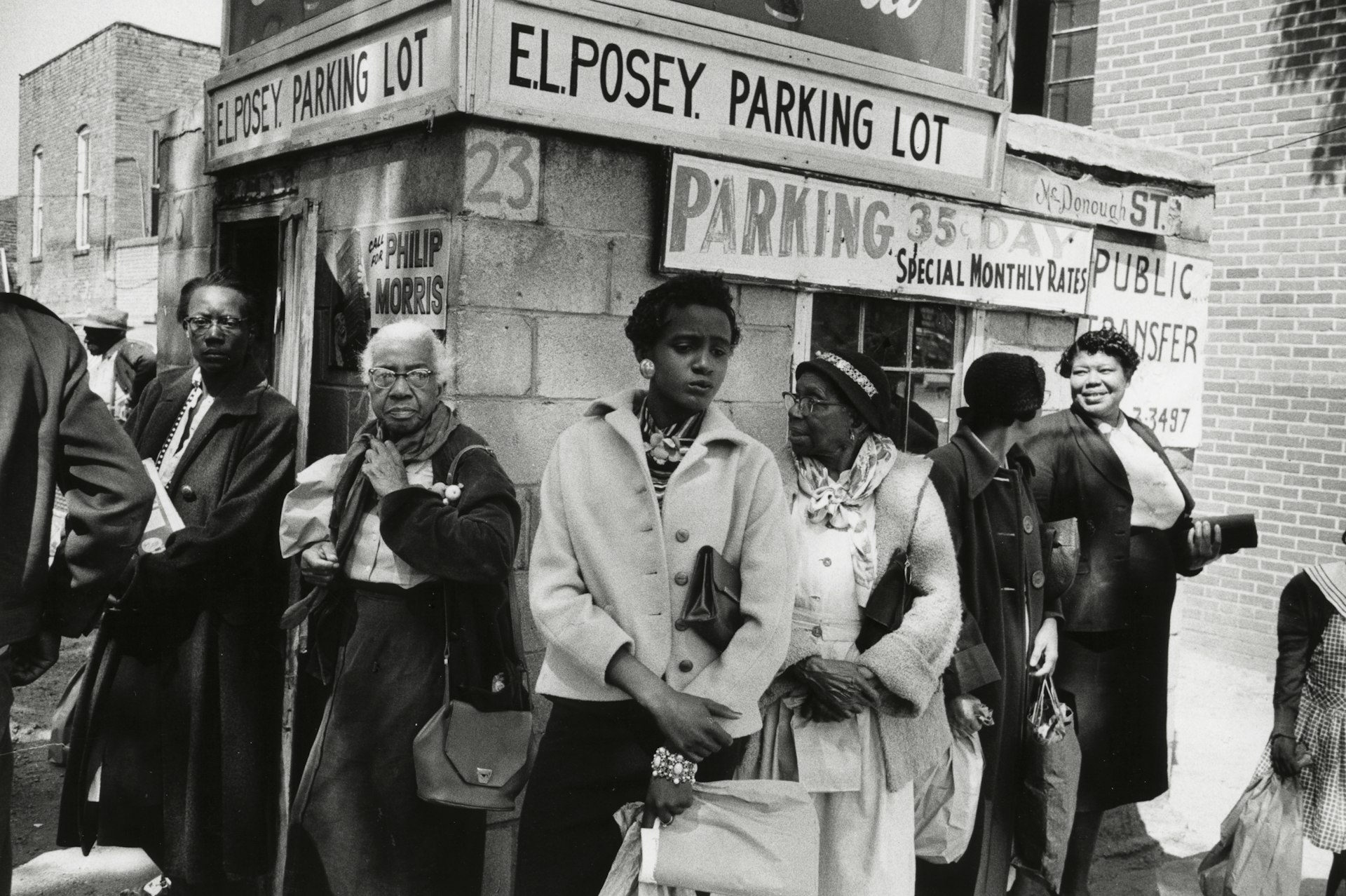

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk