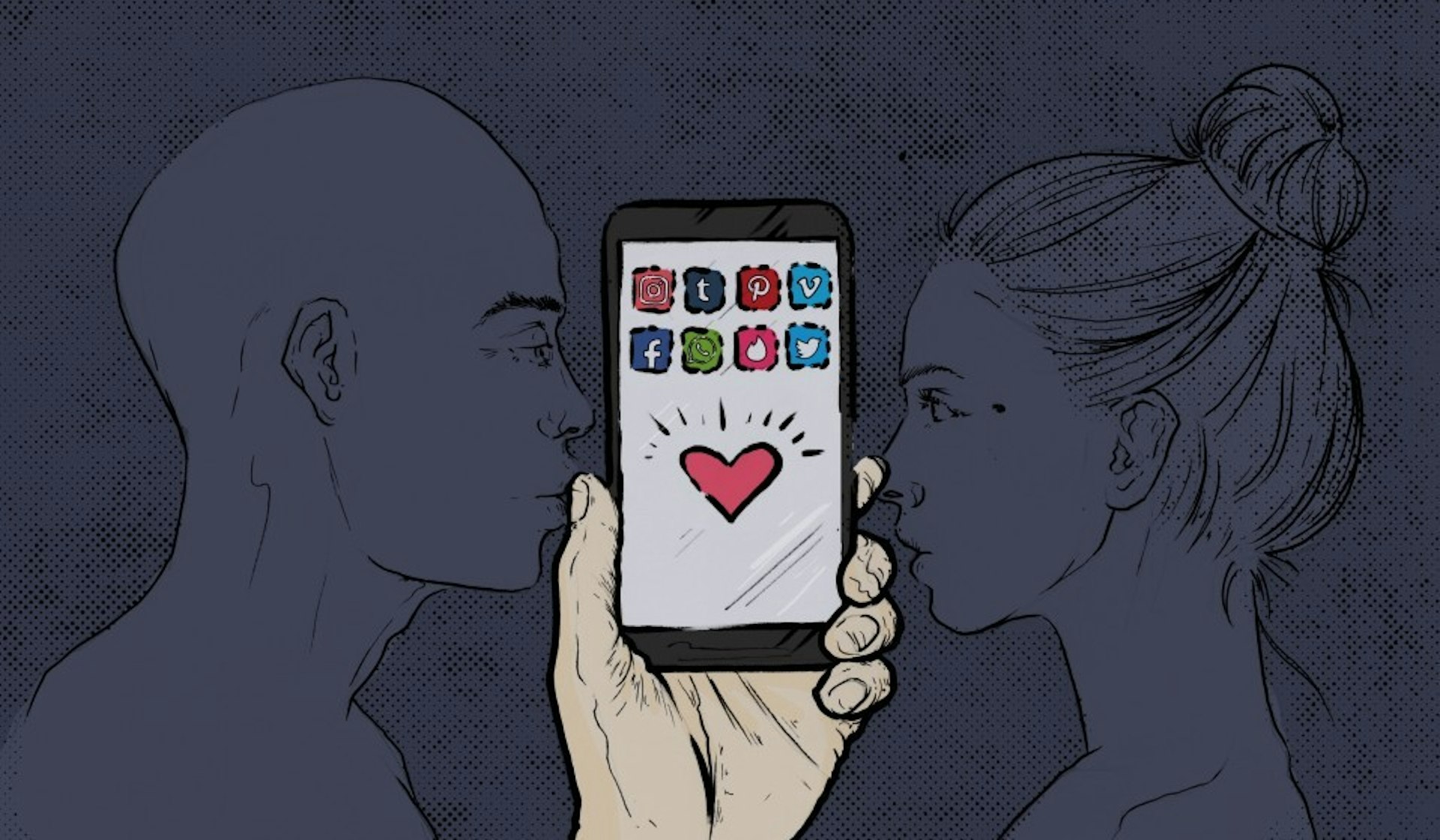

Why is our quest for validation online becoming so desperate?

- Text by Emily Reynolds

- Illustrations by Sophie Mo

I nearly died this week. This isn’t hyperbole: I really did almost die. A UTI – yet another unavoidable memento of a completely disastrous love affair – turned into a kidney infection; left untreated, my heart rate and temperature soared and I ended up being resuscitated in hospital.

I thought a lot while I was there: there was nothing else to do and I didn’t sleep for four days, and I was also surrounded by death. I thought about bodies: their stupid fragility, how they can so easily be broken and so easily remain unfixed. I thought about the man who had landed me there in the first place, my vitals monitor showing the spike in my heart rate the second he came to mind, the tightening in my chest and the nausea that flushed from my stomach to my throat suddenly and strangely measurable on a screen I couldn’t look away from. Obviously I thought about pain.

When I first arrived at the hospital, I was in pain – a lot of it. Having been coached via WhatsApp from GP surgery to taxi to A&E by someone four time zones away, I could barely speak through sobs when I was finally attached to the first of many drips. Sat in bed awaiting transfer to another ward, I did three things: I called my mum. I messaged my group chat. And I tweeted a picture of the drip, a dark joke to a close friend: “lunch”.

There’s something compelling to me in the public dissection of pain – even in its simple broadcast. We do it every day: when we’re depressed or we’re heartbroken, when we break our legs or scrape our knees, we often feel the urge to document it, to proudly present it like a school project at the front of a classroom. We hear a lot about how social media drives us to share a highlights reel: narcissists all, the theory goes, we only show what makes us look good, what makes us seem like better people. What that doesn’t account for is how desperate we can be to share our sorrows, too.

There were many photos I didn’t share, or at least that I shared and then deleted several minutes later, feeling too vulnerable. A picture of my hand with a needle inside it, stuck down with medical tape and leading to an IV; my face covered by a mask that allowed me to breathe; a dark bruise that slyly spread from beneath a tattoo on my wrist.

One – the jackpot – showed it all: my left arm, pale and scarred, and a battered hand, cannula tinged with the faint whisper of my blood. It was all there: the failures of my physical body, the depths of my mental despair. I wanted to post it everywhere.

It wasn’t that the pictures themselves were vulnerable – they weren’t, particularly. It was more that I felt my motivations were too transparent, my need for affirmation or validation too desperate. “I am in pain,” I felt as if I’d typed. “Won’t somebody just see it?”

In her book Mayhem, Sigrid Rausing writes of the addict’s desire for acknowledgement, quoting Orwell’s 1984: “perhaps one did not want to be loved so much as understood.” This, to me, goes some way to explain my urge to share moments of failure, grief or distress online.

Because for me, the compulsion to post pictures of my punctured arm or the cannula stuck to my wrist comes from the same place as my refusal to crop out the self-harm scars from my selfies, to baldly return the stares of strangers on the Tube when they notice my fucked up arm. It’s about being seen: a desire for those crystallised moments of pain, so evident on my body, to be parsed as something meaningful, something solid, something that actually happened.

But, of course, it’s never enough. How could it be? No number of replies or likes, no en-masse outpouring of sympathy, could ever mitigate those moments of sublime, disassembling pain. What can a reply that says; “Ouch! hope you’re okay!” really do, other than making us feel slightly more real, slightly less uncanny? It’s easy to blame the internet for this, the disconnect between our physical bodies no more obvious than when it comes to the workings of those bodies themselves. But it’s not a failure of technology at all: it’s a function of pain itself.

Because moments of pain – the truly excruciating kind, the kind that makes you a mindless, amorphous scream of a person – are by default completely solitary, intensely personal. It’s a fundamental incompatibility between pain and the world – “the radical subjectivity of pain” Elaine Scarry describes in The Body in Pain – that makes companionship impossible in those moments, not technology.

Sometimes you’re not technically alone: sometimes you cry for your mother and she’s there, holding your hand or scraping back your hair. But though you keep trying – keep crying for your mother, presenting your bruises to nobody in particular – nobody can ever inhabit a moment of pain with you: it always has to be suffered alone. Sometimes you cry for your mother and your mother is there; she can comfort you, yes, but she can’t ever make the pain stop.

Follow Emily Reynolds on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.