Inside the late teenage years of Basquiat

- Text by Alexandra Genova

New York of the late ’70s was a squall of dilapidation, dirt and danger, through which souls drifted, buildings blazed and bankruptcy loomed. It was a city coming apart at the seams; riven with violent crime and awash with homelessness. But amidst the precariousness of daily survival, artistic communities – in their rawest form – were thriving.

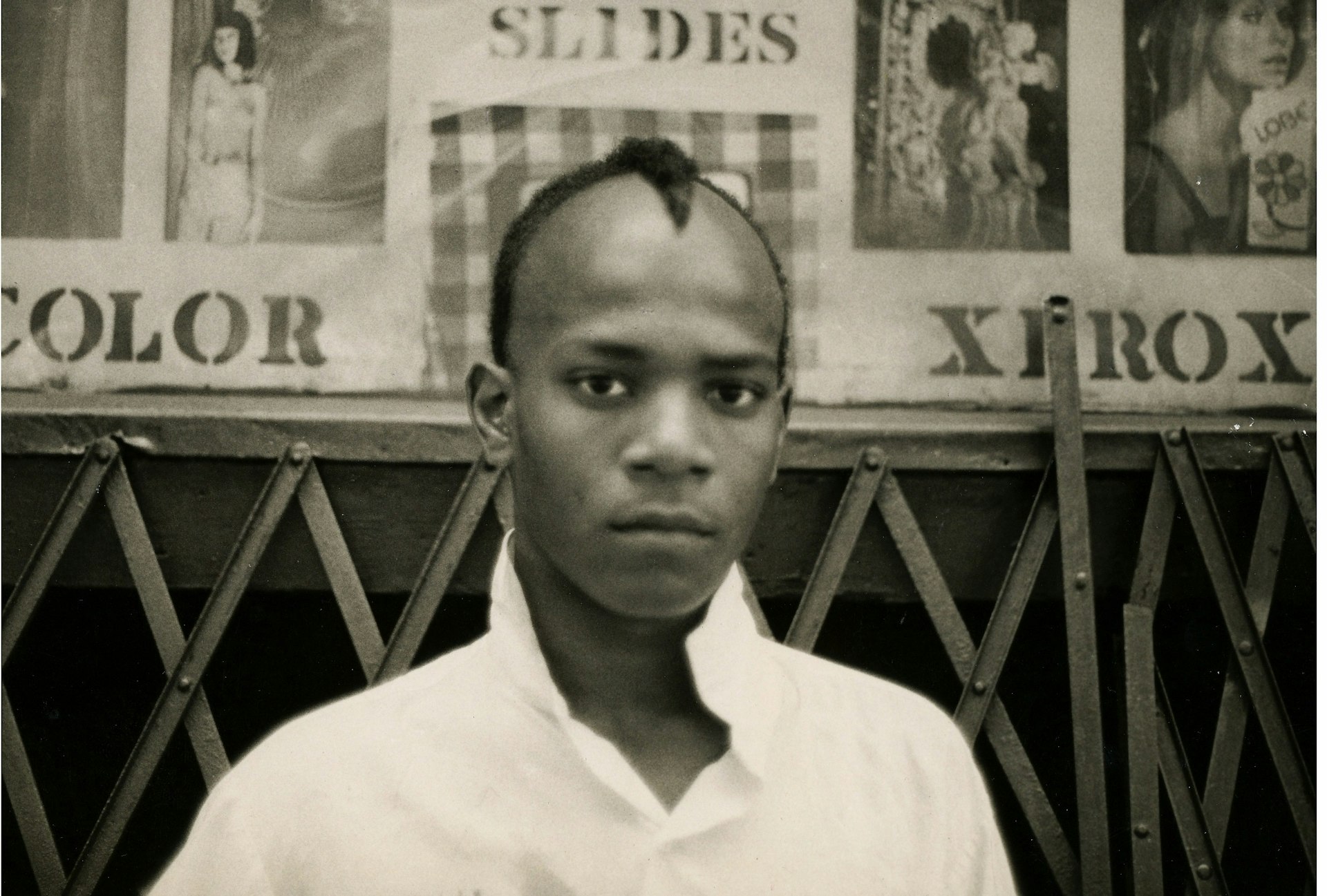

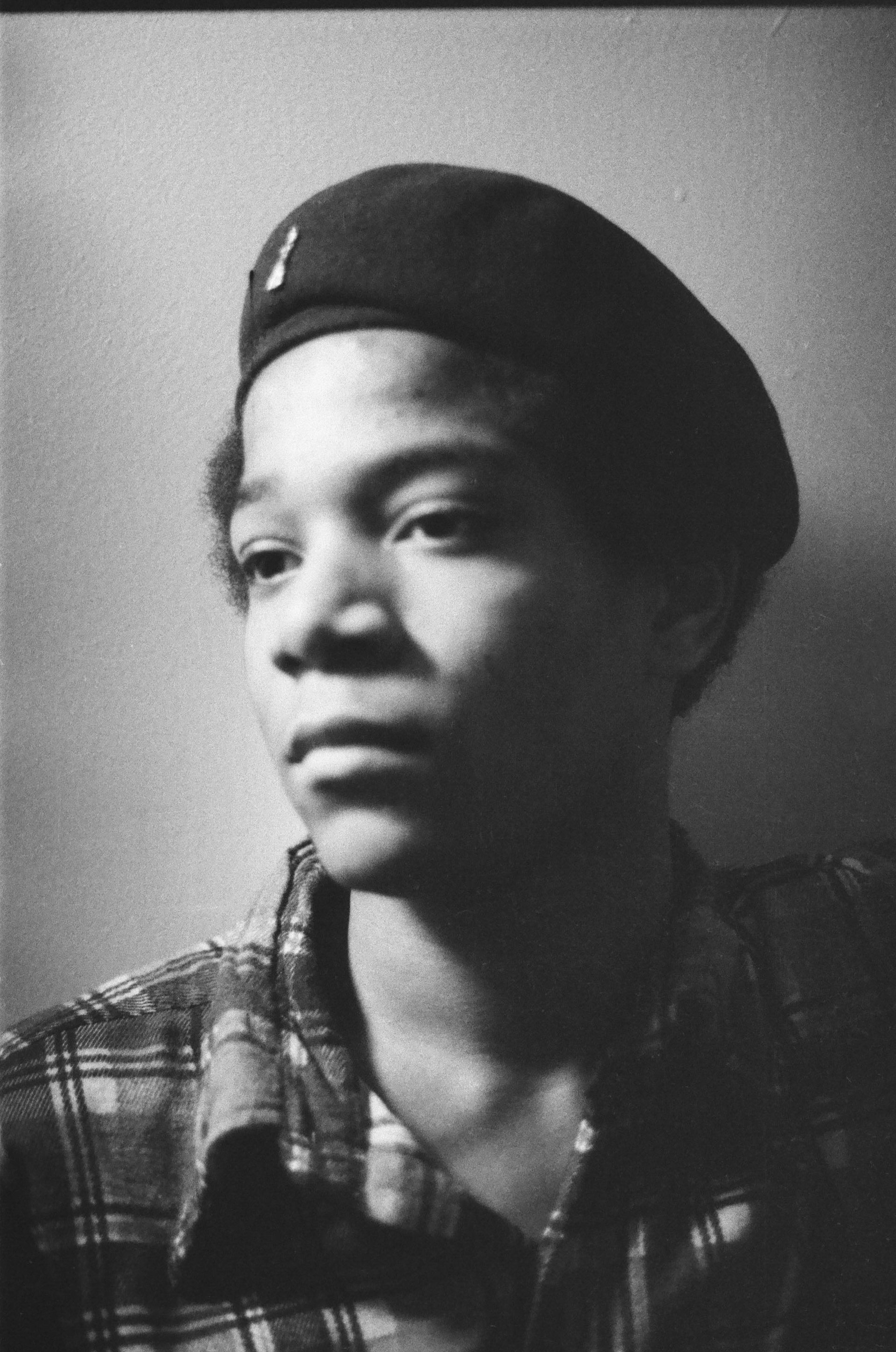

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in this so-called “City of Fear”, and used this chaos as creative fuel. In a new documentary called Boom For Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, its director Sara Driver paints a portrait of the early years of the artist (between 1978 and 1981; pre-art boom, pre-Warhol), through the environment and people that nurtured him.

“It’s what nurtured all of us,” says Driver, a lynchpin of the downtown New York art scene and a contemporary of Basquiat. “We were living in a very dangerous city but we were all kind of digging it too. It gave us great freedom because we could try all these different things. There was a lawlessness that allowed us to make movies without permits, without insurance. We didn’t even think about things, we just started shooting.”

The disorder engendered a genuine connectedness, a rarity in today’s virtual reality of social media. Micro-climates of culture bloomed, from hip-hop to punk rock to graffiti, the latter of which gave Basquiat his inaugural platform. At just 18, he joined heads with graffiti artist Al Diaz and the ‘SAMO’ moniker was born; a witty, sideways stab at the ‘Same Old Shit’ that pervaded American culture and the art world in particular.

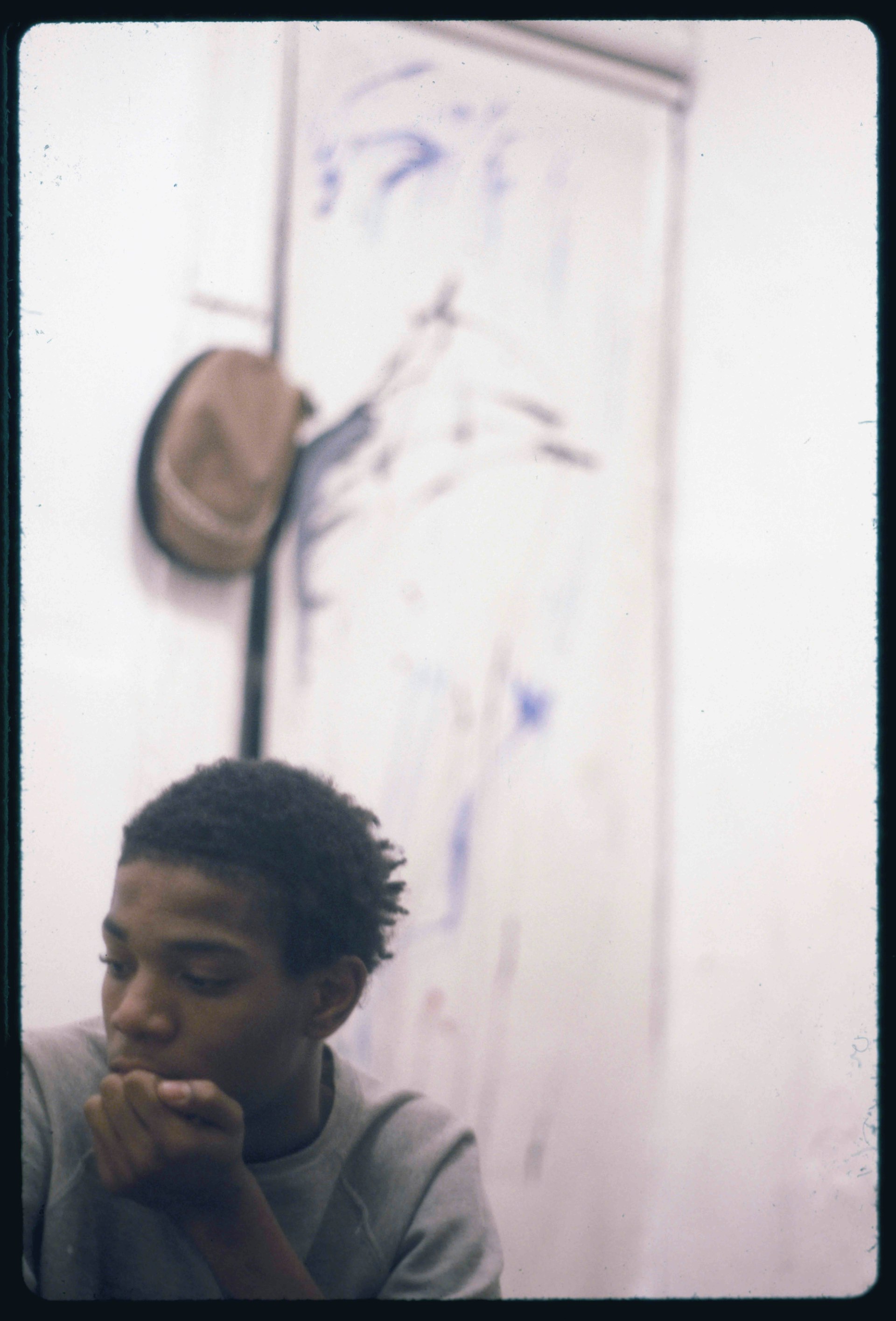

The graffiti scene that exploded in New York City at that time inspired Basquiat and fellow downtown artists to take control of things on their own terms. But Boom for Real shows how Basquiat never rested on a particular movement or medium, and instead embraced them all. He sampled punk, politics, commercialism, cartoons, clothes and more. He painted on floorboards, fridges, TVs and detritus from the street. “He was very prolific; he never stopped working,” says Driver. “He had a need and an inner, interior drive to express himself.”

Driver made the film, in part, for young people establishing themselves in the arts today, who she wants to “break out of the corporate system and get off their iPhones.” She laments the lack of communication on the streets in modern cities, where people are “not being present in their environment” and instead are “looking at these little screens and not observing anything that might be kind of cool around them.”

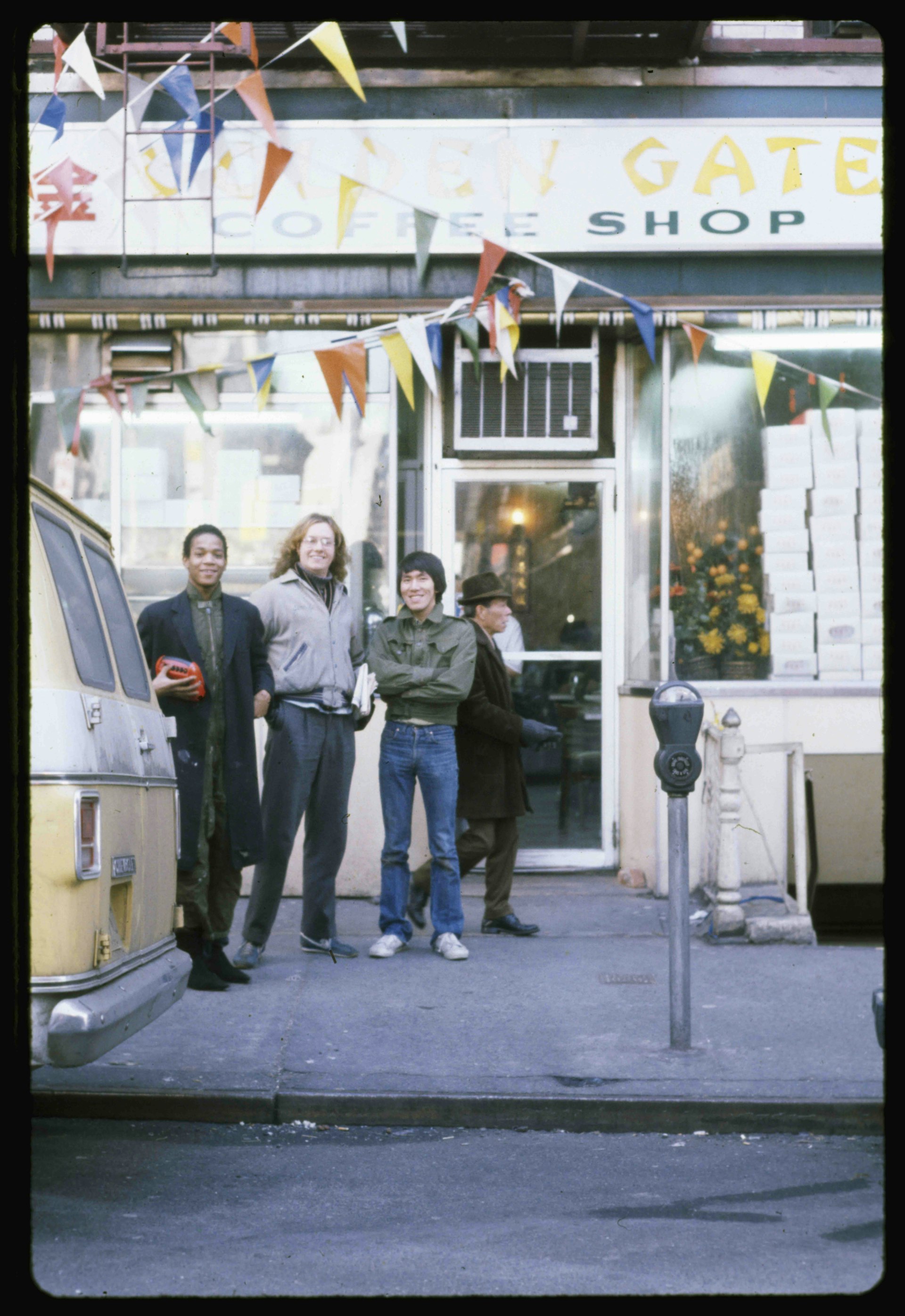

In contrast, New York of the late ’70s and early ’80s came alive on the sidewalk. Sculptors, musicians, painters and beatniks were all communing and learning from each other. “There was something quite beautiful about the exchanges on the street,” says Driver. “You had an antenna where you could feel danger, there were people you should say hello to and people you shouldn’t say hello to. It was an emotional thing; the contact between us and the street.”

The city may have nourished Basquiat but so too did his friendships. It seems fitting, then, that those friends whose couch he crashed on and who pollinated him with ideas, form the backbone of Boom for Real. Indeed, the way the film grew and developed echoes the spirit of that time. Friends such as Nan Goldin, Jim Jarmusch, James Nares, Fred Brathwaite (aka Fab Five Freddy), Lee Quiñones, Luc Sante, and many more contributed to it and helped form its rich intimacy. “It was a very moving process,” says Driver. “All these people – some who knew me, some who didn’t – gave me this material and allowed me to build this world.”

Much of the artful footage of Basquiat was shot by Michael Holman, a musician and filmmaker, who founded the band ‘Gray’ with Basquiat. “We were all making experimental movies of each other and [Holman] had the ones of Jean,” says Driver. Meanwhile, Alexis Adler, an embryologist and former girlfriend who shared her apartment with Basquiat between ’79 and ’80, provided the bulk of material that was the genesis of the film’s creation.

In 2012, Adler rediscovered what is now called a “treasure trove” of Basquiat’s art objects, notebooks and ephemera, as well as more than 150 photographs she took of him, all of which had been kept in a safe in the basement of her building. “It is an incredible collection of material that shows the beginning of a young artist and an opportunity to learn his process,” says Driver. “I always wondered about the charts and graphs [in his artwork] – they came from her science books.”

Driver wants the DIY spirit felt during those early years to live on today. “The world was a really scary place, just like it is now, but by having music and putting that fear into art, it was a great way of getting rid of it,” she says. She tells young artists to create community by hosting performances, screenings or art fairs and simply start talking to each other more. “Don’t wait!” she adds. “You have to do it; you can’t wait for somebody else to do anything.”

The investigative rawness of Basquiat’s work is part of what makes him an enduring presence. But he would have been invisible without restless ambition and a fertile New York that turned his ambition into success. As a Puerto-Rican Haitian kid who spent much of teenage years with very little money and no access to the white-wash art establishment, he had to shout to be heard. “He really broke the colour barriers,” says Driver. “I think some of the great artists are somewhat prophet-like, and he’s one of those.”

Basquiat: The Early Years is released in the UK on Friday.

Follow Alexandra Genova on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.